Having college-age kids means constant focus on college admissions, decisions, and campus culture. It’s hard not to compare my kids’ experiences with my own first run at college. My kids have all proven to be very traditional when it comes to their choices: SEC schools; Greek life, business major, spring break trips, the whole thing. I’m proud of them and their choices, but they don’t have much in common with me at that age. Growing up in a University town, I wanted nothing to do with any of that stuff. I wanted the opposite, to opt out.

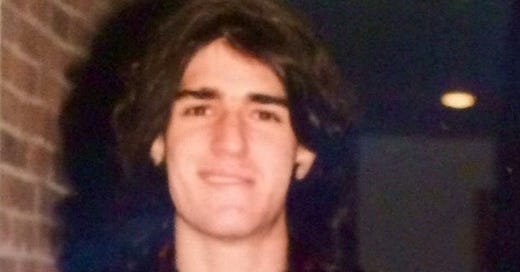

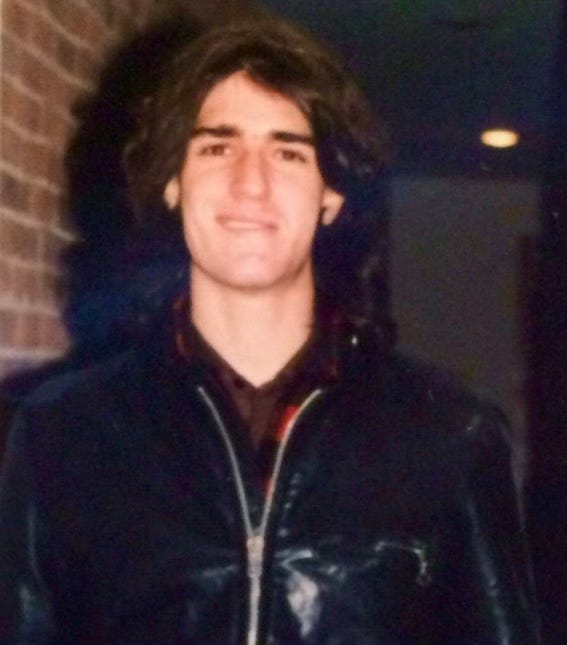

I found my identity in a local hardcore scene as a punk kid. I played in bands, put on shows, rode my skateboard everywhere, obsessed about music. I found community, love, lifelong friends, everything I ever wanted.

I had a tough, isolated adolescence as a shy kid in a University town. I had a few friends, spending most of my time in the basement practicing my drums. Then I fell into the hardcore scene, which became my first friend group. It was everything to me. The scene was where I learned to play in a band, to build an identity as a musician. Even as my musical tastes evolved and expanded, I loved the sense of belonging. I longed to build my life around that sort of musical community.

As high school came to a close, all the college talk made me anxious. My academic parents cared deeply about education. I had demonstrated over many school years that I didn’t really share their values, or at least that I couldn’t navigate that world. Many of my neighborhood friends got into elite colleges. My older brother went to an elite college. I had neither the grades nor the interest in anything like that. I believed I’d flunk out if I stayed in town and went to Indiana University, all the smartest kids from my high school flunked out of I.U. They couldn’t change their habits as they leaned into their newfound freedom, screwed around. I thought that could be me. I needed to get out of town.

I told my parents I wanted to learn audio engineering, which was partly true. I bought into the cliche at the time that a musician should have some sort of “backup plan.” If I couldn’t be a successful musician for my entire life, maybe I could make people’s records. I visited a few audio programs, including I.U., all of which seemed really technical and science-focused. I didn’t want to study physics; I wanted to start a band and make an album. I needed a cover story to get me to a city with a music scene.

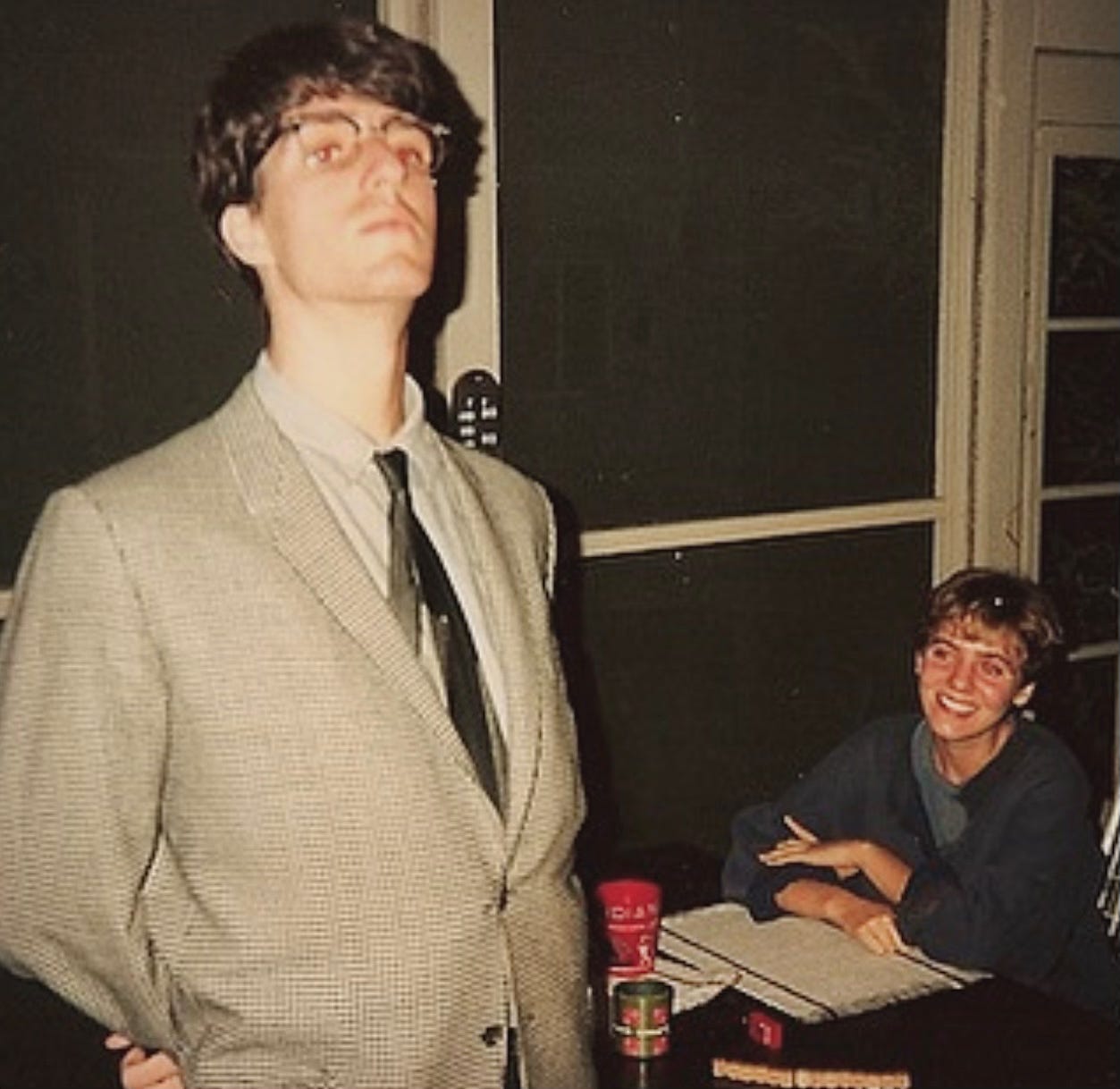

I visited Berklee with my dad senior year, spring of ‘85. I knew at a glance it was for me. I couldn’t believe the chaos around the urban campus in Boston’s Back Bay. The neighborhood was so vibrant, alive, a little dangerous, and loaded with musicians of every type, from grimy rock scene people to austere conservatory nerds. Everyone carried instrument of some sort up Boylston Street between the two buildings that made up Berklee’s campus. It felt like the center of the freak musician universe; in other words, my dream come true.

My mom dropped me off at the dorm and I faced the bracing reality that I truly didn’t know a soul in Boston. I spent the first week so hanging with everyone on the hall before I started narrowing down my circle to people with whom I actually shared some actual musical DNA. I didn’t try to relate with the guys who loved Frank Zappa, Steely Dan, or jazz fusion, none of which interested me. I cast myself as a punk, a contrarian, an outcast. I found my people through my hairstyle, wardrobe, and especially the band T-shirts I wore. Lou Reed/Velvets, Husker Du, Replacements, R.E.M., Black Flag, X…I was a walking billboard for my musical taste, which made making friends a lot easier.

Berklee felt very tribal in those days. Did you ever see The Warriors? Instead of the Baseball Furies and The Lizzies, you had the metal guys (in pink spandex and hairspray), the bebop purists (in sharp suits and Wayfarer shades), and a ton of Japanese guys who played “jazz funk.” Berklee’s student body included very few women, about one in ten. Guys would go out in packs on the weekends stalking college parties looking for dates, often frustrated to find that typical college women didn’t want to talk about Rush or Allan Holdsworth. I made friends with a blonde keyboardist from Minnesota, making me the envy of my classmates. A guy approached her and asked why she bothered to hang around with me. He said, “don’t you know there are a lot of better guitarists here? I’m better than that guy.”

I guess I’m probably one of a few Berklee dropouts to graduate law school and pass the bar. If there are more I’d like to meet you! Here’s what I can tell you. For me, Berklee was significantly more difficult than law school. My foundational music education was insufficient, so I had to scramble to catch up. It was like I imagine law school would have been if I’d been learning English as a second language. I worked very hard my first year, especially my first semester, before Freda moved to Boston. I originally applied as a drummer but I decided to major in guitar. I practiced 6 hours a day, and I studied another 2 or 3. I never ate breakfast before my performance exams because I was too anxious to digest anything. I grew up a lot that first year.

Berklee began in the 50s as Berklee School of Music, more of trade school than conservatory. Then in the 70s it earned accreditation as Berklee College of Music, able to award a bachelor’s degree. In the mid-80s, the academic classes felt perfunctory, taught by adjuncts from random nearby universities. The core music curriculum, in contrast, provided a great foundation in theory, ear training, arrangement, harmony, and focus on a principal instrument. I immediately started distilling my lessons into my approach to songwriting, which became my main focus. If I wanted a successful band, I’d have to be able to write great songs. I knew then as I know now, great songs are always the key.

Berklee didn’t offer a songwriting major until fall of 1987, after I left. I had a great guitar teacher named Jon Damian, a traditional jazz guitarist who also happened to be a wild conceptual artist. Gregarious with a big bushy mustache, at our first lesson, Jon handed me a copy of The Inner Game of Tennis, which I needed to read cover-to-cover before the next lesson. I thought he was joking, but he clearly meant it. The book is a classic text on mindfulness, applicable to any sort of performance, including music.

I wasn’t a great student for Jon because I didn’t really want to “play tunes,” as he called it - improvising on standard tunes. I wasn’t serious about learning jazz. I told him I wanted to write songs. He said if I wanted to write, I had to keep pushing myself to learn. Jon told me people write to their ability: the more music you know, the more sophisticated your writing. I kept that in mind as began writing songs. Did I even want to write sophisticated, jazz-influenced songs? The truth is I wanted to keep my songs on the primitive side. None of my favorite songwriters used those fancy-pants jazz chords. Nevertheless, to his point, as my musical vocabulary grew, my songwriting evolved.

For example, with Blake Babies songs I co-wrote with Juliana, I typically wrote the music and handed it off to her to write lyrics and adapt the melody for her voice. I wrote the music for the song Out There just after I dropped out of Berklee. For the most part, the harmonic structure of Out There is very simple and repetitive, a very common 1 4 5 progression. But listen to the bridge. There’s the Berklee damage, jazzy chords to change the vibe. It’s one of the best musical sections I’ve written; it makes the song, takes it to another level. To Jon Damian’s point, you use the colors on your palette. I had to have a reasonably sophisticated understanding of harmony to write that bridge, and other sections like it. I didn’t have any desire to write like Steely Dan, but I did want to write evocative progressions that could make people feel a certain way. My Berklee education expanded my palette.

My favorite class in my short time was a songwriting workshop with Pat Pattison. I’ve learned over the years that Pattison is revered in the professional songwriting community, with many successful writers among his former students. Taking Pat’s class coincided with finally writing songs I felt confident to share. Pat focused on lyrics and phrasing. Early songwriting efforts by both Juliana and me came from Pat’s class, his writing assignments. Speaking of Juliana…

The story’s been told more than once - Freda and I got drunk in the Berklee dorm, followed Juliana to her room, knocked on her door, and asked her to start a band. That’s literally true, but a little context helps. We’d noticed Juliana, just like she’d noticed us, because it was the ‘80s - we all wore our college rock uniforms hoping to be noticed by like-minded musicians. The blessing is that someone else, someone talented who shared our tastes and ambitions, lived down the hall. Of course we started a band together; that’s why we were there. In a broader sense, that’s why all of us were there.

I went home to Bloomington for most of the summer of 1986, but when I returned in the fall my attitude towards school began to change. Juliana and I focused on getting a strong set of songs together so we could play shows and get on the radio so we could get better shows. By spring of ‘87 Blake Babies was making a name for ourselves, and I’d also joined the better-known, more in-demand Lemonheads on drums.

I had to get my Berklee transcript when I applied to law school, and I was surprised to see that my grades didn’t drop my sophomore year. The first year is so standardized; reality sets in when you declare a major and figure out how much work it will take to graduate. I chose production and engineering, a very competitive major.

I developed a bad attitude about the way Berklee taught production (this was the 80s - the worst era in history for production). I’d found a different music community in the Boston underground music scene, one that resonated far more with my taste and ambition, my people. I simply didn’t want to be involved in the sort of production they taught at Berklee. When I thought about the work to graduate, I saw little value in a degree. My parents were happy to stop paying my tuition.

Juliana stuck around and graduated with our class. I worked low-wage jobs as we launched the band, wondering if I should have stuck it out. I got my real production and engineering education at Fort Apache, the legendary studio that produced countless great albums in the late 80s and 90s. In retrospect, if I’d have stuck around, I should have taken the brand new songwriting major. I loved making records, but I became completely obsessed with songwriting.

Would I have written better songs if I’d studied another couple years? We’ll never know. If memory serves, Juliana’s degree is in songwriting. I don’t want to make any assumptions, but I feel like we learned to write songs together, and as part of an amazing songwriting community that included some of the greatest writers of our generation, from Evan Dando to Black Francis, Jay Mascis, Dean Wareham, Bill Janovitz, Tanya Donelly. We listened to records and imitated our idols until we found our own voices.

I spent a few years as a Berklee dropout before deciding to go back to college to get into law school. As it turns out, dropping out was a good choice. I knew I didn’t have the maturity to give Berklee my all, and back then I just wanted to squeak by with a B average. In my second attempt, on my dime and with a clear goal in mind, I became an A student. The only reason I graduated from UAB Cum Laude instead of Summa Cum Laude was the anchor of my mediocre Berklee grades. I became ambitious and competitive, and I carried that through law school. What changed? I think I’d finally internalized the lessons from The Inner Game of Tennis, a decade too late.

Berklee’s a different kind of institution now. It’s hard to think of another example of a college that has gained so much prestige in a generation. Hardly anyone had heard of Berklee back then, now it’s respected as an elite program - especially since the merge with the Boston Conservatory. Several Rounder artists went to Berklee as professional musicians to gain prestige and formal training. It’s a proving ground for many of the best bluegrass and acoustic folk musicians from all over the world. Berklee has also become a respected music business school since I attended, though I doubt it would have occurred to me to study music business had it been an option. It took a few semesters in the School of Hard Knocks to truly pique my interest in the business side of music.

I’ve never regretted my short time at Berklee. It delivered completely by setting me on my path to a career I’ve enjoyed. I still relish those opportunities to deliver my one-liner that always lands with a certain audience: “I went to Berklee…and dropped out.” Like so many others, from the very famous to the hopelessly obscure, I’m a proud Berklee dropout.

Thank you for this great post! There is so much food for thought. Following the imperative of the authentic self is rarely a linear path. There are usually starts and stops and side trips and decisions that end up feeling "close but nope". Only in retrospect do we get a deeper understanding of the thread we were following and the particular forces at play at the time. I loved so much hearing about how everything brought you here and that nothing was wasted. The full four years at Berklee were not what you needed, but it expanded your artistic language and palette and introduced you to some life long friends and inspiring colleagues. People called to work in the arts usually have such amazing human stories—full of passion and courage and determination to become and live into their truest selves Thanks again, I read this outloud to another musician while we were traveling this weekend. What a great conversation it inspired about all the roads taken and not taken, about having compassion for what we knew and didn't know at the time, about the relationships that changed our lives, and about what is so powerful and transcendent in the arts - that on wonderous, determined, strong or shaky knees we followed.

Love the back stories. Dropped out of Curry College’s Communications program due to a combination of serious illness and I’d learned all they could teach me. I was already on-the-air part-time at an upstart “alternative” station in my hometown. I only had 18 credits left to graduate but I couldn’t be bothered. Worked full time menial jobs until I saw an opportunity to make WFNX a full-time thing. Quit my day job to drive to Lynn everyday for no pay & did every fill-in shift for $6 an hour. Two-and-a-half months later my dream job was mine.