Kurt Cobain’s work means a lot to me. I never met him, but we were both part of the same big underground music community in the 80s, long before he became a massive rock star in the early 90s. He came to my band Blake Babies’ show in Olympia in 1990. He liked us enough to invite us to open the first leg of the Nevermind tour, but that’s a story for another time (*spoiler: we didn’t do it). My hero appreciating my band’s music meant a lot to me. It means a lot to me now, as Cobain’s music still resonates so many years on - both with me and countless millions around the world, across generations.

Juliana Hatfield of Blake Babies wrote a song titled Nirvana for one of our records that came out just before Nevermind. We listened to Bleach on cassette at least once a day in our van for an entire U.S. tour, our first full tour that almost killed us. The music got us through.

I’m fascinated by this idea about Cobain and TikTok. I’m not sure I understand the meme posted above, which I assume is AI slop. As a GenX’er, am I the audience? Am I supposed to feel validated? The statement is obviously, irrefutably true. Kurt didn’t lip sync on TikTok - because he died over 20 years before TikTok existed. There’s a deeper implication here, though. I’m not quite sure what it is, but I know it’s deep. Very deep. Deeper than the Holler, as it were.

I think the point is, regardless of whether he lived then or now, Cobain is too cool to lip sync on TikTok. I actually agree. There’s a huge difference, however, between “lip synching on TikTok” and using social media to connect with an audience. I feel strongly that Cobain and most of the significant figures from the grunge era would have embraced social media if it existed then. Forget about all the thirst traps, flagrant self-promoters, and AI slop. TikTok and YouTube are the best way to spread outsider culture with no filter. Why photocopy fanzines when you can make little movies to watch on your phone?

I make the point because there’s an attitude in some corners of the indie world of looking down on all social media content that falls within marketing. I find that ridiculous, because social media has been a miracle for independent music. We used to have to sell our copyrights for nothing to shady companies trying to sell out to the highest bidder. Now a great young band with a work ethic can build an audience at near zero cost on social media, then they can turn the audience into customers by way of reputable digital services that charge next to nothing. Once the audience is locked in, there’s never been a better time to be indie. That’s largely because of social media.

As a member of a semi-famous underground in the 80s and early 90s, I can tell you that bands of the era didn’t become successful by accident. They weren’t plucked from obscurity. They chased it. We chased it. You learned the business however you could, and you worked all the time to make things happen. You did what you had to do to build an audience, which meant figuring out how to record, how to book a show, how to get on the radio, how to get people to write about you. Nirvana did all these things.

Nirvana made their connections, built community, build an identity, and created an audience. They worked their asses off; it’s well documented in numerous books and I’ve read most of them. Dozens or hundreds of bands of the pre-Internet era did all those things. For a lot of reasons, including being geniuses, Nirvana broke through. Don’t tell yourself it was by accident or without enormous effort and investment of time, money, resources, and discomfort. Ask his former manager Danny Goldberg and he’ll tell you. Better yet, read his book. Cobain was very ambitious. He chased it all the way until he got there and realized he didn’t want it after all. Therein lies the tragedy, the struggle.

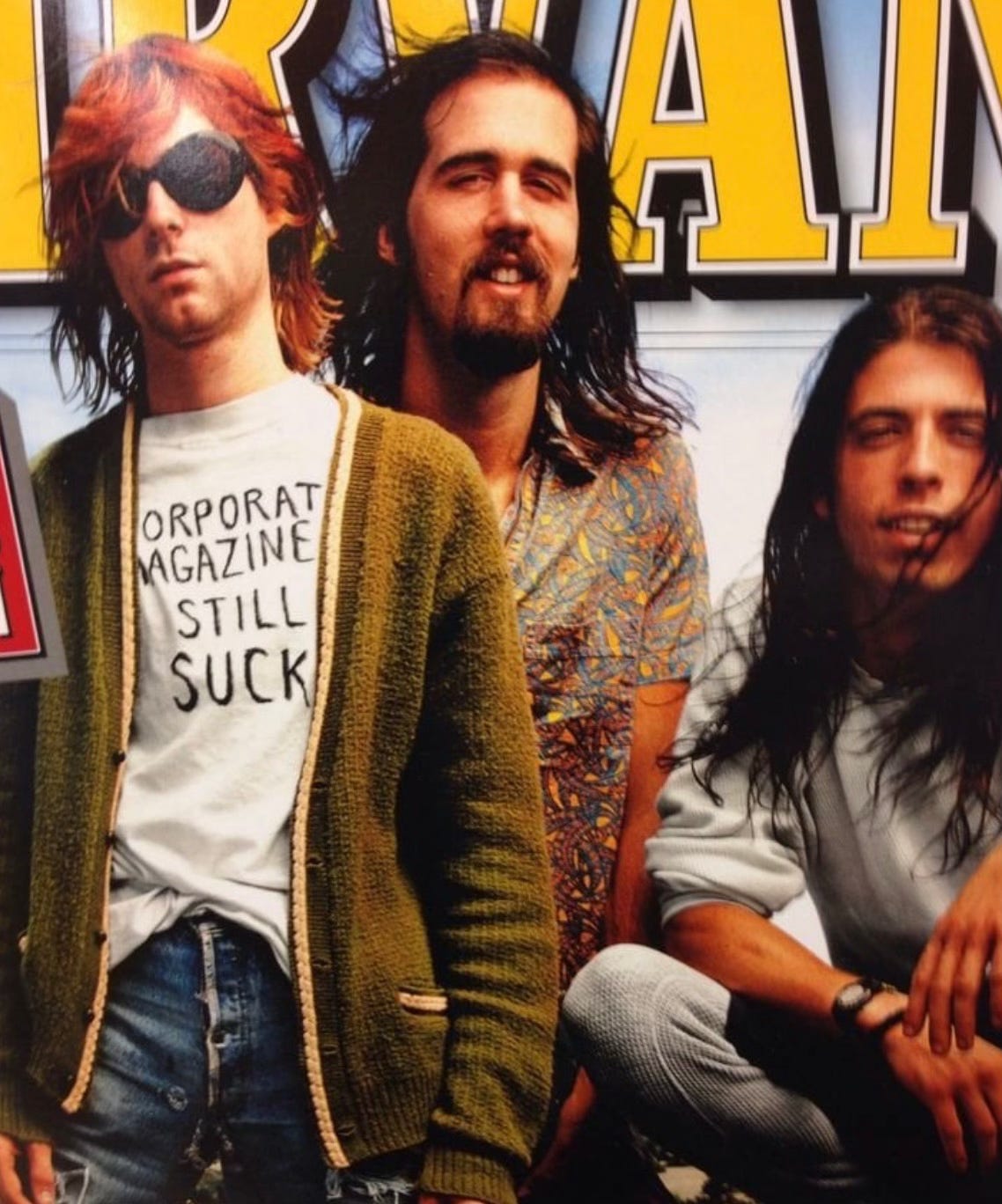

To be clear, Nirvana was a punk band with a punk attitude. I’m absolutely convinced they didn’t form to be the biggest band in the world. That thinking wasn’t in the culture of the 80s underground. Punk and punk-adjacent bands didn’t court mainstream success, because mainstream success wasn’t possible - until it eventually was, thanks to Nirvana. Nirvana’s image straight through was about low effort, the opposite of careerism, stumbling into stardom. Don’t be fooled. Kurt on the cover of Rolling Stone in his Corporate Magazines Still Suck T-shirt - irreverent and iconic. Back then it was a punk statement (cribbed from the SST Records slogan “corporate rock still sucks”), and it was shocking at the time - for about half a second. You can elevate punk rock to the mainstream and still wind up part of corporate monoculture. As a longtime fan of pre-fame Nirvana, I loved post-fame Nirvana just as much. Nevertheless, as of 1992, they ceased to be an underground act by any definition. They became media stars, because that’s what massive fame looked like in the monoculture.

It’s hard to compare that culture with today, thinking of all the things we had to do to build an audience compared with the things musicians have to do today. It’s so different. People know so much more. I don’t remember ever discussing a “marketing plan” with our label, or being invited into those meetings. We talked about some aspects of marketing such as radio promotion and publicity. We knew the drill, we wanted bigger shows and more money. But “marketing” never came up. We certainly didn’t call it marketing when we put up fliers or dropped off radio tapes at college stations. But it was marketing. All of it.

Now artists are their own label, their own head of marketing, their own creative director and content creator. They know so much more, and they have the language for it. Nobody knew jack shit about the business in the 80s. I didn’t even really read the contract I signed with Mammoth Records in 1989. Other than four albums and some dollar figures, I had absolutely no idea what any of it meant. I had a lawyer who didn’t explain it, but then I never asked.

I remember when my interest in the business finally emerged in the mid-90s. A book changed everything for me. I used to read a lot on tour. What else was there to do? I’d read everything by certain authors, classics, science fiction, The Beats, Existentialists, etc. I met a guy, the brother of a Boston musician, who worked as an editor for a major publishing house. He sent me books he edited. He’s David Dunton, the editor of Donald Passman’s Everything You Need to Know About the Music Business. He sent me the first edition. I read it, then I read it again. That flipped a switch. If that book hadn’t found me, I doubt I’d have gone to law school. I had a latent interest in the business, but it wasn’t in the culture to care about the business. We’d rather just sign contracts we didn’t understand. Thankfully, that is changing.

Just as if I were a music lawyer in the 80s I wouldn’t waste my time on an act that wouldn’t go on tour, today I’d be very hesitant to work with an act that eschewed social media. From my experience, most people under 40 - which is pretty much my entire clientele - have no issues with artists sharing work on social media. It’s the olds who look down on it - particularly TikTok - with their fixed understanding that it’s a bunch of adolescents dancing and lip synching like they used to do on Musical.ly.

The two most successful projects I’ve worked on in the past 5 years have had the same basic social media strategy: film the shows, edit posts with the most compelling moments from the shows into bite-sized snacks, and share on multiple platforms. Imagine if Nirvana were touring in the age of TikTok, with the chaos happening on stage every night. It would be an act of immense generosity to share those transcendent moments. It’s why you have all these newly-minted arena acts that don’t get played on the radio. Come to think of it, you know who’s pretty good at that exact TikTok strategy? Foo Fighters.

Although I believe artists can still be subversive, wild, unpredictable, and inspired on social media, the incentives have changed. Definitions of what is “cool” have changed for younger generations. Remember how much we all used to care about cred, our indie culture bona fides? Well, cred is dead, if it ever mattered. In the age of AI, we’ve lowered the bar to the point where literally any living human creator has baked-in authenticity. Now the credibility standard goes like this: “Was it made by an actual human?” Meanwhile, nobody cares what Pitchfork reviews anymore, and nothing has filled that void. Nobody needs it; nobody wants it. Kids like what they like, and more likely than not they found it on socials.

I’d love to test this claim by going to a bank and asking for a loan. They’d ask, “What’s the collateral for your loan?” I’d say well, I joined The Lemonheads in early 1987 just before they released Hate Your Friends on Taang! Records; I played the album release at TT the Bear’s. I wrote a bunch of songs with Juliana Hatfield, and I did a bunch of shows with Pixies and Dinosaur in the 80s. Yeah, that’s right, before they got sued and became Dinosaur Jr.” “OK,” they’d say. “What does that have to do with collateral?” I’d raise my voice and shout, “Isn’t it OBVIOUS? My indie cred is unimpeachable! It must be worth millions!” Nope. My indie cred, such as it is, something I worked so hard to achieve for so many years, is worth zero…at least for purposes of securing a bank loan. Or a record deal.

All it represents now is that I’m old as f***. The experiences and perspective that come with it, however, remain the foundation of my career. Here’s what I can tell you after nearly 40 years in the trenches. All those bands from the 80s and 90s who had success, the ones with the iron-clad indie cred, in their own way they chased it just like all those kids posting on TikTok every day. They worked their asses off to connect with an audience. I had a meeting with a young artist yesterday who has found himself in a label bidding war. His high-profile manager found him while scrolling TikTok. He saw a video, recognized the talent, then got involved and started opening doors. If that artist hadn’t put himself out there, he wouldn’t have these incredible opportunities. That’s the lesson. Serious artists, then and now, figure out how to connect with an audience, build a team, and do the work. These days, most likely, the most powerful tool for their development is social media. The result is a power shift away from labels towards artists.

Look at the cover of Passman I posted above, the Big News in the 11th edition: find out why artists have more power than ever in the industry. Now you know, and you don’t even need to read the book. If you’re a creator and you’ve read this far, you should read it anyway.

Everything you say about the indie hustle is true, but part of indie cred was acting indifferent to the audience — maybe it was shyness or a genuine “I don’t give a shit,” but it was real. It’s hard to imagine top performers today going on tour and behaving the way a lot of indie bands behaved in the 90s.

Never met any of the band members. I only saw Nirvana 2x. Because I worked out of the office that managed ‘Nevermind’ mixer Andy Wallace, I was one of the lucky few in the audience for their MTV: Live & Loud performance. It was just before or just as the album was breaking. The band knew what they had accomplished & Kurt was filled with joyful abandon.

The only other time I saw them was at NYC’s Roseland Ballroom on November 15, 1993. Having The Exploited’s John Duncan on board as second guitarist really messed with their chemistry. Plus I’m an empath. It was pretty clear to me that Kurt wanted to be anywhere else but there doing anything else but what he was doing. He was THAT not into it.

I was so disturbed/put off by the vibe Kurt projected from the stage I spent most of the concert downstairs seated in the lounge until the show ended. I was waiting on friends who had come down from Boston specifically for the gig.

Was extremely sad but not terribly surprised to learn of his suicide less than six months later.