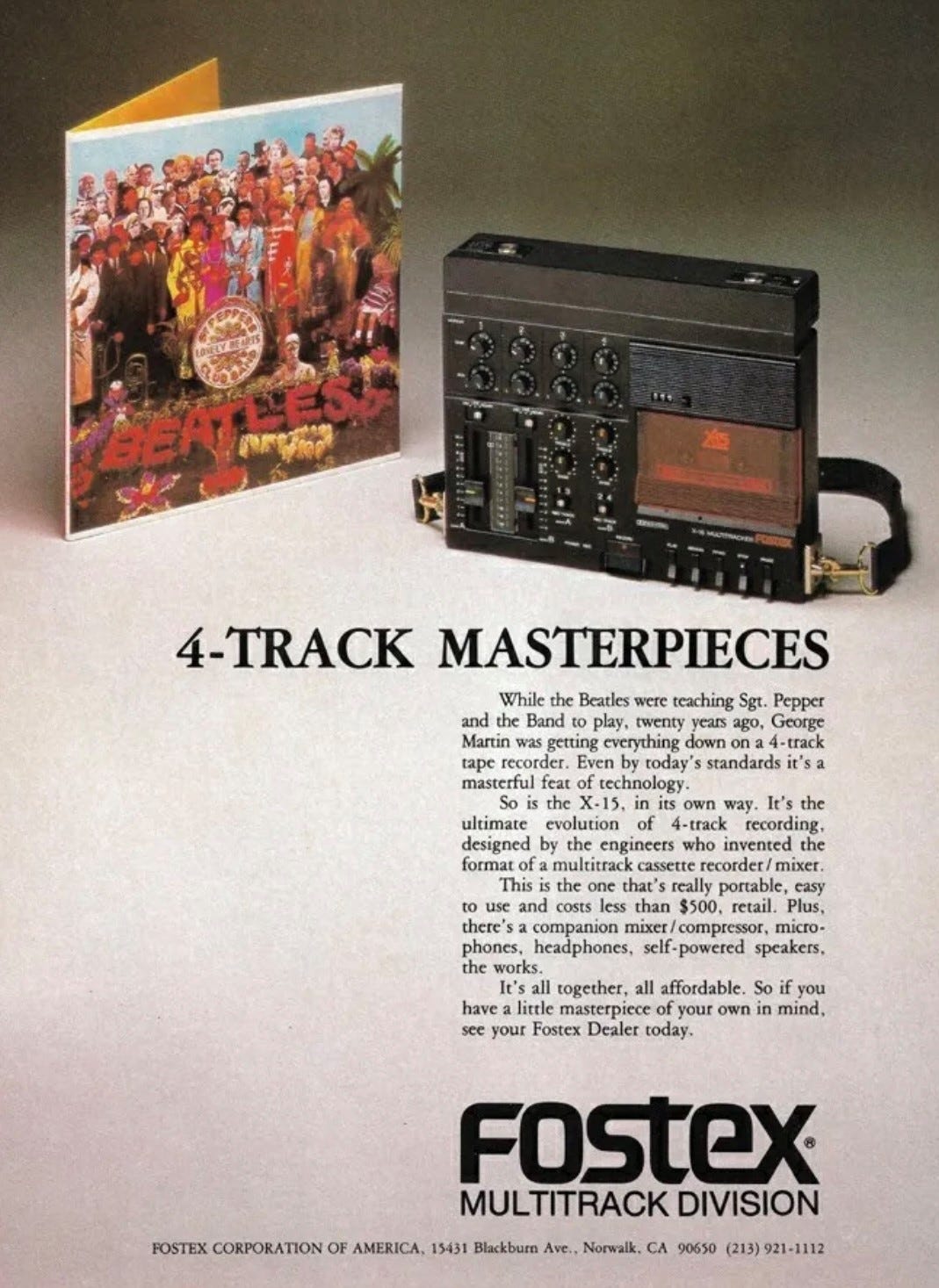

Do you remember this early 80s magazine ad for the Fostex X-15 home four-track studio? Even as a high school kid, I knew it had to be bullshit. I mean, it’s technically true that The Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper on a four-track tape recorder (or, rather, a series of 4-tracks synched together). They were not, however, four-track cassette recorders meant for consumers and hobbyists. Their machines were state-of-the-art, studio-grade professional machines in a top London studio (Abbey Road, naturally) operated by Geoff Emerick, one of the greatest audio engineers of all time.

I wasn’t fooled by this advertising slight-of-hand; however, I did have very high expectations regarding the potential of 4-track cassette recording, specifically because I was obsessed with Nebraska. I just finished reading Warren Zanes’ wonderful Deliver Me From Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska. It’s fantastic…anyone interested in the intersection of technology and culture should read this book, whether or not you care about the album. But if you also love the album, you’ll probably read it in a single sitting like I did.

I recently asked my older brother and father how we had a copy of Nebraska when it first came out in 1982. I’d completely forgotten the story, but my brother - who had very little interest in music prior to his early teens - went through an intensive period of music discovery, beginning with the Beatles through the British Invasion, many iconic artists from the 60s and 70s, and eventually settling into a lifelong Springsteen fanatacism. He bought the Nebraska LP for my dad for Christmas in 1982, and it became the most played album in our house for many months. By 1984 we’d all become huge fans, and one of my greatest memories of that period was a family pilgrimage to Chicago’s Rosemont Horizon arena to see Bruce & the E-Street Band on the Born in the U.S.A. tour, but I digress.

I came up loving arena rock, and I knew a few Springsteen songs from the AOR station out of Indianapolis, WFBQ, Q-95. I bought a lot of slightly damaged $1 albums from the local store, so I owned both Born To Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town, but I never went deep into the albums. I listened to the song Born to Run, and Badlands from Darkness, and that’s about it. That’s pretty much how I listened to music as a kid: I listened to the songs I already knew from the radio. I remember in 5th grade it took me months to get around to listening to side 2 of Led Zeppelin II, and I was surprised that it was just as good as side 1.

By the time Nebraska found its way to our family turntable, I’d abandoned arena rock for punk and hardcore. I wanted everything to be loud and aggressive. But I was immediately fascinated by the sound and vibe of Nebraska. One of the many great points Warren Zanes makes in his book is that an arena artist just off a world tour in support of an album (The River) that produced his first #1 hit (Hungry Heart) releasing an album of rough home recordings of dark songs about marginal characters was punker than anything actual punk musicians were doing at the time. But I didn’t see it that way; to me, there was punk and everything else. But somehow those songs got through to me. Maybe it’s because I grew up on a steady diet of Bob Dylan records, or maybe the dark stories resonated with me. But man, it really stuck.

I knew from the liner notes that it was recorded on a 4-track cassette machine, and that intrigued me. It didn’t sound bad, but it didn’t sound like other records. It sounded real. It was the sound of isolation and despair, and that was where I wanted to be. I was just beginning to play guitar, and I learned basic chords playing along with those songs. The first song I ever learned to play and sing was Open All Night. I can still play all those songs from memory. Every single one. I wanted to write like that, I wanted to make a record that sounded like that and made people feel the way Nebraska made me feel. That was over 40 years ago, and in a way I’m still chasing that ambition. I think a lot of us are.

One revelation is from Zanes’ interview with Matt Berninger, the lead singer of The National. Berninger notes that Bon Iver’s debut, For Emma, Forever Ago is a direct descendant of Nebraska. My relationship with For Emma is about as deep as it gets. I received that album as a demo tape in 2007 from BI leader Justin Vernon’s 19-year-old manager looking for a lawyer to negotiate a recording agreement. I heard that music without any real context, and just like Nebraska, it became an instant obsession at the start of my ten-year professional relationship with Bon Iver. Berninger pointed out that it was the same setup: one man with a guitar and a microphone, in isolation in the dead of winter, making a masterpiece. I’m surprised I never made that connection, especially since each album has a permanent place among my very favorites. They’re completely different, but somehow very much the same.

Nebraska was front-of-mind for me when I started making my own four-track recordings in the late 80s and early 90s. Four tracks gave rise to an entire genre of “low-fi,” with many of my friends and peers defining the style that eschewed expensive studio recordings in favor of the raw immediacy of noisy, ultra-compressed 4-track sounds. I wasn’t really part of that, because I never felt my own 4-track recordings were good enough to release, and from the time I started making records in my late teens, I always had access to professional studios. By the time of For Emma, artists like Vernon could create far superior-sounding recordings at home using hard disc formats such as ProTools. Low-fi was a brief moment in history, but it was a collective obsession of all my underground music peers trying to get the best sound possible out of this extremely limited format. I suspect we all held up Nebraska as the ultimate achievement of four-tracking, while failing to understand that Bruce and his production team spent enormous amounts of time, effort, and money in mastering to get Nebraska to sound as good as it does. It’s a perfect record, and the inspiration for so much great music to follow.

As a final thought, the best-known song I’ve ever written is probably Girl in a Box from 1990, in which I take creative license to assume the voice of a psychopath. I’ve tried to write in character many times, to tell fictional stories in songs, and it rarely works. But with Girl in a Box, I felt I could do that specifically because of the song Nebraska, about Charles Starkweather’s 1950s murder spree across Nebraska. Springsteen assumes the character of Starkweather, inspired by Terrence Malick’s 1973 film Badlands, which Bruce happened to see on television. I’m not comparing my song to Bruce’s in quality, but it came about the same way. I saw something on daytime TV and I wrote about it, from the point of view of the deranged criminal. It felt completly normal to me to do that, but I remember being shocked when I realized what Nebraska was about. I wanted to be shocking, and I felt empowered as a young writer to assume a voice that was absolutely not my own, to get closer to the subject matter and the motivations of a criminal. I was under the direct influence of Tender Prey by Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, but it was Nebraska that taught me I could do that.

I think I’ll organize my attic and see if I can find all the 4-track mixes I made and never shared. It’s probably mostly self-indulgent crap…but maybe there’s something worth sharing.

I would totally buy a download of something called John Strohm: Mostly Self-Indulgent Crap. And I'm not kidding. Mistakes, wrong turns, and false starts all have something to offer.