In The Death Spiral

I think it was SXSW 2006, maybe 2007…the Crisis Years in the music business. I was an aspiring music lawyer: already practicing at a law firm, not yet handling music deals. I attended every music business panel I could as I soaked up as much knowledge as possible. It was a fascinating time of great urgency and anxiety.

The panel, a CLE (lawyer) panel, was about the 360/ancillary rights deals the major labels had recently started rolling out. In addition to revenue from record sales, labels sought - rather demanded - to participate in additional income streams such as touring, merchandise, and even music publishing.

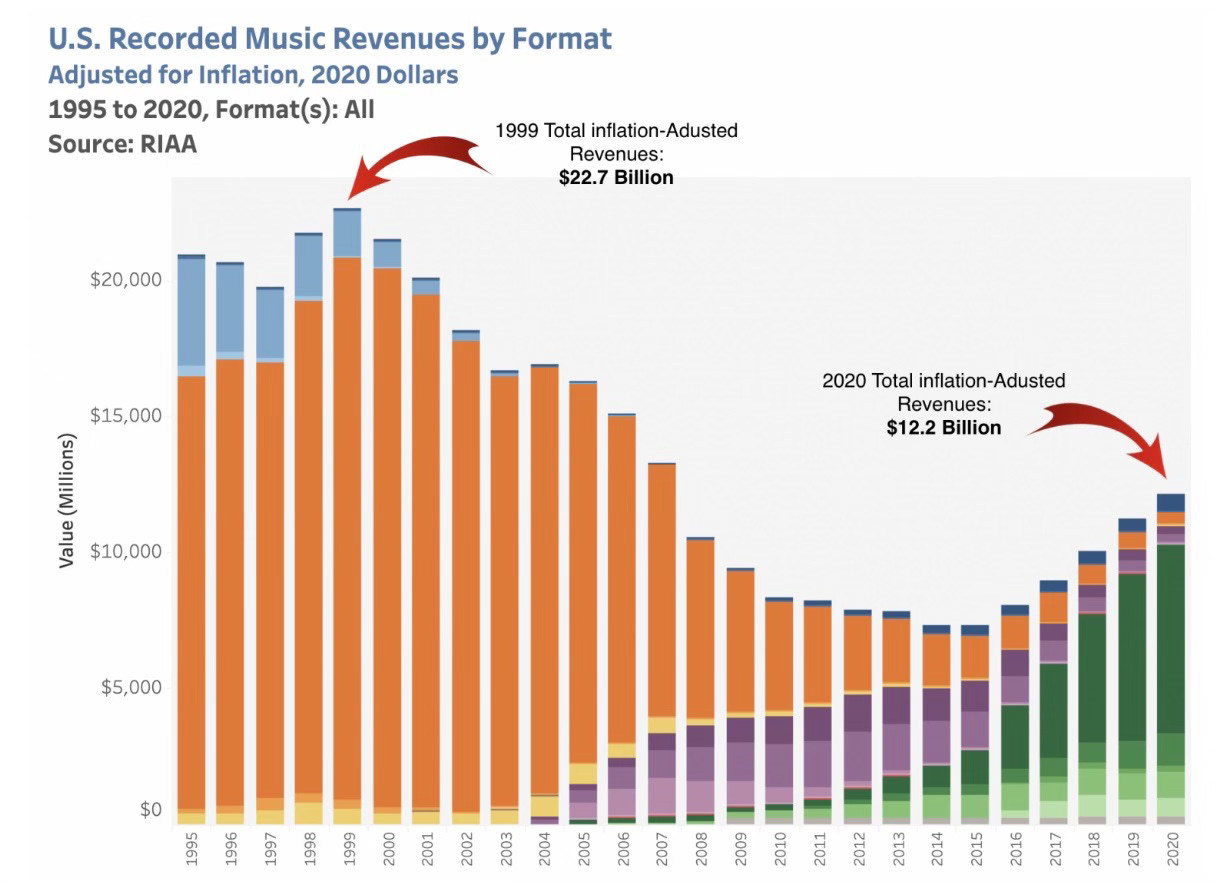

Popular domestic streaming services hadn’t yet launched, and CD sales were in steep decline. iTunes sales didn’t make up the difference, as revenues had dropped by more than a third since 2000, from over 20 billion at the peak to around 15 billion and dropping - a bloodbath.

In a Q&A after the panel, an audience member asked why artists should agree to these deals when record labels didn’t really contribute any direct value to these ancillary revenue streams such as touring. A senior lawyer for a major label confidently replied. “You should do these deals because you need for us to survive.” He continued, “Without us, there is no music business.” The audience erupted in taunts, jeers, and eventually laughter. Did he really just say that?

This was a radicalizing moment for me that permanently shaped my opinion on the major industry. From my perspective as a recording artist who came from indie music and had bad experiences with a major label, I couldn’t believe such hubris and lack of self awareness. I thought, if that’s their world view, they’re doomed. Need them? Of course the business can survive without majors. In fact, I thought, artists would be better off without major labels, who extracted far more value than they added. With the changes on the horizon, seeing the consumption model taking shape, I wasn’t wrong.

In 2007 I had my first real artist client, an indie pop band that was the flagship act for a well-regarded indie label that has thrived for over 30 years. My client had recently broken out from the indie rock pack and reached the level of touring theaters, playing ticketed shows in major markets to several thousand people. Their arrangement with the label was simple: the label modestly funded, released, and promoted the albums, as artist and label shared all profits 50/50 under a license (as opposed to full ownership). A typical indie deal, then and now. The label didn’t participate in any revenue other than record sales and licenses.

My client felt that their band had begun to crack the mainstream, and they wanted to explore possible opportunities with majors. I’d never handled a major deal but I was on board to find out. I called an old friend, an obsessive music fan who had worked in A&R at a couple different companies for over a decade. We’d become friends when he pursued one of my bands in the early 90s, we bonded over music while enjoying a few nice meals on his employer’s dime. He followed the indie world closely and loved my client’s records. I regarded him as an artist advocate.

We discussed my client’s goals, and he became excited. “We’re gonna crush this,” he said. He saw an opportunity for a visionary signing of an emerging superstar.1 I thought wow, this is so easy - it’s going to be so much fun to negotiate the deal with the label this excited! This will be innovative! A&R guy said I’d be hearing from the label’s lawyer soon with an offer.

That’s when I saw my first 360 deal proposal in the wild. The first, and also the last for a long time. It wasn’t competitive with staying the course with the indie, quite the contrary. Low money, full ownership of masters by the label, a bunch of options without firm commitments (meaning the label could either keep the artist under contract for many years or cut them loose at their whim), and a whopping 25% participation in the band’s gross touring and merchandise revenue…a truly insane proposal on every level. It’s funny in retrospect; but at the time just deeply disappointing and embarrassing since I’d built it up based on the feedback I’d received from my A&R friend. I called the guy to ask what happened. He said, well, the lawyers have certain guidelines they had to adhere to...every deal’s 360 these days. Nothing he could really do about it, but how about I respond and try to get it to where my client would sign. We chose not to respond to the offer and politely passed.

The next year, when my roster grew to include a few true breakout acts like Bon Iver, possibly the biggest mainstream breakout in the genre. I didn’t bother to send Bon Iver music to any major labels. What was the point? An artist like Bon Iver could (and obviously did) make a fortune on an indie label. A major would have had the opportunity to insinuate itself into the creative process, while an indie such as Jagjaguwar would give an artist the resources they need and get out of the way. I handled dozens of record deals between 2008 and 2012, and none of my clients even expressed interest in a major. Back then, “indie” music was almost entirely on independent labels. All the major offers that came my way seemed to presume that they were intrinsically more valuable than anything an independent could possibly offer. Perhaps I was in a bubble, but it seemed obvious to me that the music industry would do just fine without major labels.

Naturally, once Bon Iver broke internationally, majors came sniffing. That would be true of any independent that achieves superstar sales. But not until it was a no-risk proposition.

Back to that 360 offer, I want to put a fine point on just how ridiculous and insulting it would have seemed to my client with an indie-centric worldview. This is an act - much like my own bands in the 90s - that built a following brick by brick, tour by tour, under lousy conditions, relying on press and word of mouth to build a solid 7-figure business. The major label wanted to take what would have been over $1,000,000 off the top of their touring and merch, ahead of management, ahead of the agent, so that the artist would go from netting millions to potentially netting next to nothing - all for the privilege of being on a major and without any clear sense that they could deliver anything the indie couldn’t. Additionally, the label would own the recordings and have options for a decade, likely along with some measure of creative control.

With the benefit of hindsight, the only explanation for such a staggeringly bad offer is that the major label didn’t consider the indie its competition. As I’ve witnessed, they didn’t understand the model, and they regarded these companies with a measure of contempt - even as they began to enjoy major commercial success. The A&R guy - a true music fan and artist advocate - would have loved to make a competitive offer. We talked about it for months, he described the offer he wanted to make. He understood the competition and its appeal, even as the label’s leadership did not. The lawyers, under the direction of the label’s leadership, calculated that the artist would be seduced by the mere fact that it was a major label - never mind that their brands had become tarnished in the independent music communities.2

The Rebirth

All of this occurred just before the rebirth of the recording industry with the rise of streaming and the consumption model of today. I handled a number of major deals between 2012 and 2017 when I left law practice to run Rounder, an independent label owned by Concord, which is a multi-billion-dollar music company built acquisition by acquisition using private capital.3 Doing A&R for Rounder, I quickly got my wakeup call that with the rise of streaming, the major label game had very suddenly changed.

I felt that I knew my competition. Based on my own direct experience, I hadn’t considered that I’d be competing with major labels. Then in 2018 I threw everything I had at trying to sign emerging Appalachian singer/write Tyler Childers to Rounder. To my surprise, we were outgunned at every level by RCA. Not only did they offer to write a bigger check, seemingly they beat us on deal terms as well. As has since become the norm, they offered terms previously unheard of from a major. I expected competition, sure; but from other Indies. They not only competed, they blew us out of the water. They had the resources, and now, in the streaming age, they had the data to see that Childers would be a multi-billion stream artist in a matter of a few years. Today, his top ten Spotify streams add up to over 3 billion, over 10 million in revenue. That’s the world we’ve increasingly lived in ever since.

These days it’s getting even tougher for an independent label like Rounder, because major labels have completely changed their business model in the age of consumption. I’m sure 360 deals still exist, but I haven’t seen one in years. Labels tend to sign viral acts, acts that have a large online following. Most deals are licenses with short terms, sometimes with large, seven-figure advances. They have little in common with the aggressive deals of the past. Labels used to build catalogue from their artist development efforts. The consumption model has turned major labels into as much a service business as a way to build catalogue.

What’s The Bullpen?

So what’s the bullpen then? This isn’t a popular term everyone uses. It’s what I call a strategy that enables majors to compete more effectively with independent options. It’s similar to the strategy talent agents use of “hip-pocketing” - meaning they build non-committal relationships with prospective clients so they can sign them more easily once things fall into place. The Bullpen is an indie distributor affiliated with a major. It’s a low-cost place to corral projects with “upstream” rights for years in case they blow up. It’s a low-cost, low-risk A&R strategy.

The Bullpen is different in every way from the “fake Indies” of yore. In the days when label credibility mattered, major labels used to launch high-value developing projects on indie imprints to disguise the actual brand partner. Even if they didn’t respect Indies as their competitors, they recognized the unique brand value. One example of a fake indie is the first Smashing Pumpkins album Gish, signed to Virgin but released on Caroline. Another is the first Guns n’ Roses 1986 live EP “Live ?!*@ Like a Suicide,” signed by Geffen but released on the fictional Uzi Suicide records. The tastemakers would mistakenly assume these were authentic indie projects. By the time the real audience showed up, nobody would care about the label.

The Bullpen isn’t about branding. It’s about creating a “funnel” by signing many artists to inexpensive deals that will give the major label their pick of the acts that actually blow up. Top of the funnel is a bunch of acts; bottom of the funnel is the few the label actually calls up. I’m not calling out companies by name, but every major has their Bullpen. A typical bullpen deal is something like this: $10,00-$50,000 for an exclusive term of the equivalent of one or two albums, with a license term of 5 to 10 years. There’s rarely any marketing commitment or budget, and the distribution fee can be as high as 50%. Invariably, Bullpen deals have some sort of upstream mechanism, typically a first negotiation and matching right.4

All sorts of iterations of The Bullpen will show up in an artist’s DMs when they have a viral moment. I once had a client with over 100 suitors in the course of a week in their Instagram DM. Some of them are scams; some are actual major labels. To be clear, The Bullpen isn’t a scam, per se. It’s a strategy majors increasingly use to deal with a crisis in creative A&R, and to avoid the risk of signing an artist to a proper deal before they have an audience. It’s hip-pocketing with contractual strings attached.

Let me be clear: I have no objection to The Bullpen as a strategy in general, but there are conditions. I have no issue with first look and match rights in deals. I have no issue with a major label creating a farm system (a much more fitting description, I just happen to like calling it The Bullpen). My objection to The Bullpen is when the it’s passive, a holding pen; a well to draw from if one of their Bullpen acts has its big viral moment and is presumed ready for the big leagues.

The alternative is actual artist development: real, old-school A&R and marketing. The lazy and anti-artist approach to The Bullpen is to sign every act that pops and then wait to see what works on its own steam. On the other hand, having a minor/major system where a major label gives its independent system the resources to develop and market artists makes a lot of sense, and provides a legitimate competitive advantage over independent alternatives.

Onward & Upward

Kudos to majors: they’ve figured out - at least for now - how to gain competitive advantage over indie competitors - in part by creating their own indies. There’s no reason, by the way, indies can’t create their own version of a bullpen. Maybe they’re already on that page - Concord recently acquired the digital distributor Stem. Secretly Group is both a label group and a distributor. First look and match deals aren’t unique to the majors.

At one point in my music law career, it seemed that none of the artists I worked with had any real interest in being on a major label. Now, most young acts are open to being on a major as a way to build an international career. It takes enormous investment and resources to develop an artist career from the ground. A major deal feels like an acknowledgement as well as an open door to an exciting future. It’s rare for me to find a young act that feels a strong ideological alignment with indies; however, it’s common to think of being fully independent as “a good brand.” That’s a big change from the old days when artists feared being seen as a failure without a label brand association.

I handle these Bullpen deals all the time, and I make sure artists go into the relationship with their eyes open. If there’s no guarantee of marketing, then I make sure the artist knows they need to invest any advance money into their marketing, and I help them figure out how to hire a team. I make sure the artist understands that The Bullpen comes with opportunity costs; it’s another way artists bet against themselves. If the goal is development, you need to make sure the deal includes real development investment and resources. It feels like a tectonic shift from labels as builders of valuable catalogues to labels as service providers. Maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

I know you’re wondering. The act is still making records and touring, but their moment didn’t really last, things leveled out and eventually declined a bit. I don’t think signing a deal would have made any difference.

For much more on this topic, I recommend Sellout by Dan Ozzi, which chronicles the label feeding frenzy around hardcore and emo in the late 90s and early 2000s.

I could debate either side regarding whether Rounder/Concord is truly an independent label. Concord is a massive catalogue company that distributes its frontline labels through Universal, a major. I’ll say it’s technically independent and leave it at that.

A “first look and match” is exactly what it sounds like. If an artist wants to sign a deal, they have to first negotiate with the affiliated major for a period of time. If, in good faith, they fail to make a deal, they can obtain another offer from an unaffiliated label; however, they then must show the offer to the affiliated label and give them a chance to match the offer.

Fascinating history. Sounds like Y Combinator for musicians except VCs take equity rather than revenue streams. Everything is a startup these days!

Great article. In the past, labels were sometimes accused on paying radio stations to play their artists i.e. payola. Is there a contemporary version of that relationship between majors and the 'key' streamers (algorhythm 'fixing') or is there a level playing field for indies and majors in regards to streaming access and promotion?