Recently I had a conversation with a client who is being pursued by multiple record labels. They said they’d heard about a label on their short list paying an exorbitant sum for a lesser-known act. Would I be able to negotiate an advance that big? I said I couldn’t tell the real value of the advance unless I knew the other deal terms. They asked, “Why would that be?”

I shouldn’t ever assume artists intuitively understand this point, but it’s SO important: If you push hard for money in-pocket, you’ll probably weaken your back-end terms. I’m not saying you don’t occasionally see deals with both great terms and huge money in-pocket - that’s what we call a superstar deal. I’m saying if you have a choice - if you don’t need the money - bet on yourself. Make a budget and stick to it. Don’t let your ego cloud your judgment - bragging about record deal terms is douchebaggery anyway. Find more creative ways to be immodest.

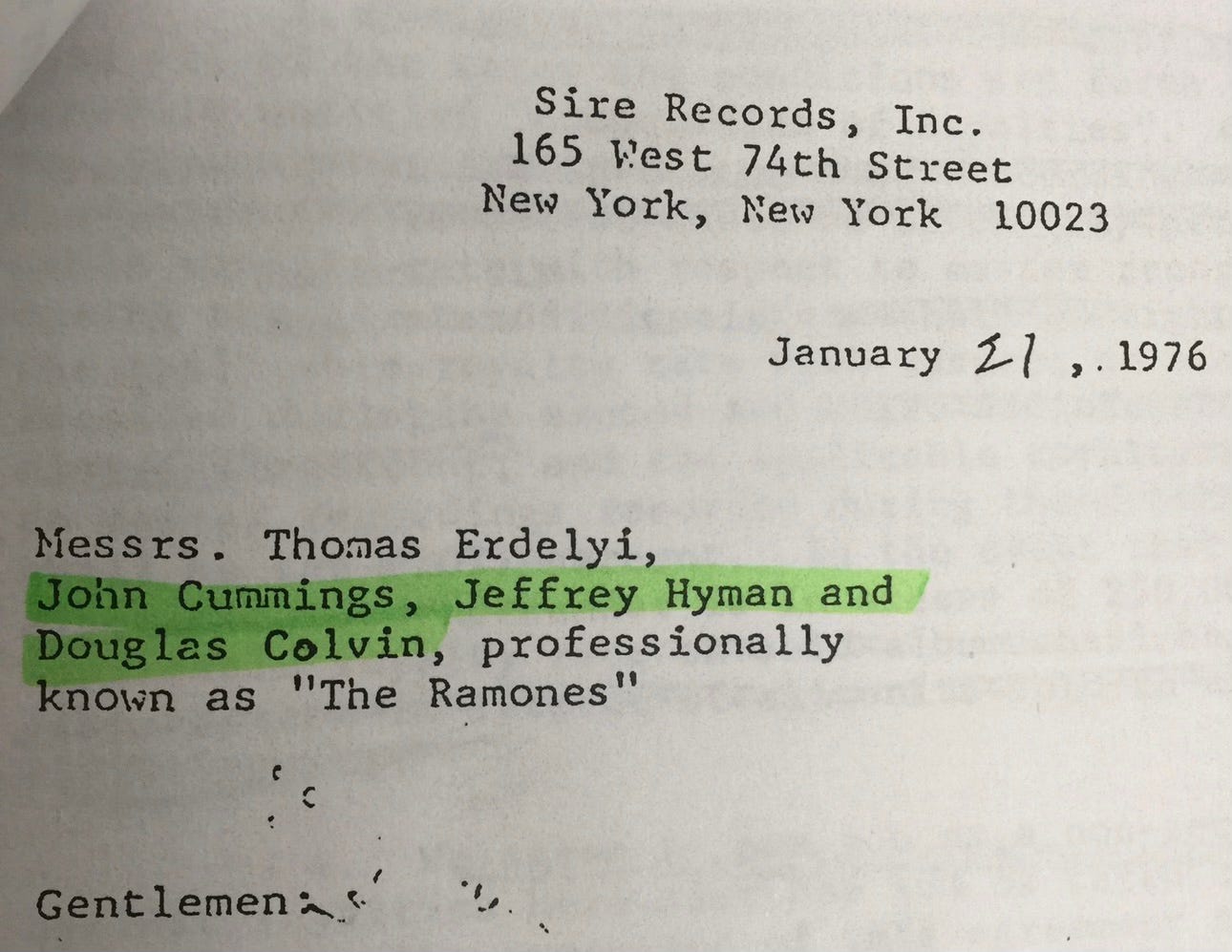

For the most part, if a label gives an artist a very friendly deal - short license, profit share, fewer options, etc. - it will mean less in pocket. Conversely, if an artist negotiates for a big advance, it will almost certainly impact the back-end terms in the company’s favor. There’s a perfect balance where everyone’s betting on success and that’s where great deals get made. That’s the Kumbaya zone, the Real Thing. Like…

So why would an indie label overpay for a developing artist. The offer usually tells the story. If a label offers a big advance with aggressive back-end terms (i.e. ownership, low royalty, lots of options), we can assume the label is making a long-term investment in the artist’s future development and earnings. If the label offers a big advance and an artist-friendly deal, it’s worth asking questions. Are they desperate for a hit? Do they know something you don’t? Like, is there A&R buzz they’re picking up on and they want to close before there’s competition?

There aren’t many secrets anymore, to be fair. Everyone’s looking at the same data and making the same risk calculation. Outliers can look suspicious - it probably translates into some sort of desperation. That’s my suspicion on the one my client asked me about. Record labels are only as hot as their most recent breakout - a few years is an eternity. Competition is so fierce these days, independent labels fall between the two extremes of the unlimited resources of a major and the unlimited freedom of a distribution deal.

It’s always interesting to see what happens when you push for better back-end terms with a willingness to reduce the advance.1 As the risk in the deal shifts, the terms may dramatically improve. It might be a relief to the label to spend less at the front end. I can tell you from experience that an executive who doesn’t plan to retire from their current job probably has less motivation to fight for ownership. If they enter into a license deal, they’ll probably be long gone before it expires.

I should add some nuance to the concept of “in pocket,” because there are several ways for an artist to get money out of a label. In-pocket funds are usually commissioned by anyone working on commission: managers, business managers, maybe even the lawyer. Advances are commissioned, royalties are commissioned, but money that’s spent on things like recording and marketing are not (or rather should not be) commissioned. In a profit share deal, these hard costs are borne equally by artist and label, whereas in-pocket monies (including tour support) are typically recouped from artist royalties.

Which brings up a huge point. As a reminder, pretty much anyone can be an artist manager. There’s no education, experience, or certification required. Lawyers have to get an advanced degree and maintain a license; accountants have education and licensing requirements too. Even agents are licensed. Managers, not so much, no bar to entry There are many great managers I’ve had the pleasure to know, but there are many more indifferent, self-interested, or bad ones. Your trust in them should be earned. 2

Artists, if your manager pushes you to front-load your deal without concern for the back-end, there’s a good chance they’re betting against you. If you’re feeling this pressure, ask more questions. If the manager is betting on you, they want a long, lucrative tail because you’re partners for the long haul. If they don’t plan to stick around, or if they don’t believe you’ll be successful, then their incentive is to get paid now.

One deal term that aways confuses people outside our industry is options. Traditional recording agreements are structured as contract periods, during which an artist will record and deliver sufficient recordings to fulfill their commitment - usually about an album’s worth. At the end of a contract period - usually about 1 year after the release of product - the label (not the artist) has the option to continue the contract for another period, another product.

As an aside, one of the funniest terms you see in every label contract is the “option warning.” The idea is when you get to the end of the period of time the label had to exercise the option, it’s up to the artist to remind the label of its rights. Then the label has, like, another month to think about it. It’s an open acknowledgement that labels don’t have their shit together. Since I’m in the music industry, you’ll see option warnings in all the contracts I draft. I’m assuming folks will screw up.

I’ve been told we have option warnings because of a disaster that occurred between the first and second Black Crowes albums. American Recordings held the contract with an option for several additional albums. Since the band signed as a baby act and blew up on its first album, the first option would have been very inexpensive, with full ownership, low royalties, etc. But guess what? They forgot to exercise the option. Then they had to negotiate for the second album without a contract and they paid millions for what I’m sure was a way less friendly deal.

That’s the sort of thing that gives deal lawyers nightmares - to be the one responsible for that catastrophic a screw-up. But you now what? Deals sucked back then. Perhaps it was justice, those brothers getting to negotiate the superstar deal they’d earned. Rick Rubin might be some sort of Bodhisattva these days, spouting wisdom at this moment on a podcast near you. Back then, he was just another suit making company-friendly deals and getting ridiculously rich. In his defense, it was the culture. But if you are enlightened in today’s music business, you need to treat artists with due respect and make deals that serve their interests and careers. That’s the Artist Business - betting on the artist.

Even if I think this is the right approach, I’ll always defer to my clients once they understand the give-and-take dynamics.

Artists, try to avoid signing a term of years contract with any manager, but especially one who doesn’t have significant clients who can vouch for them. The only thing you need to work out is how the commissions work - every other term in a management contract is to protect the manager, not the artist. Work on a handshake with no contract term for at least a year if you can.

That’s right

John, the contract Situationist/cosplay Communist/provocateur/fashion designer/neophyte manager Bernie Rhodes negotiated for The Clash illustrates many of the pitfalls you describe. If a band ever needed a savvy music business lawyer, it was The Clash. Whether they would’ve listened to said lawyer is an open question.

When it came time to do the deed, Rhodes, for some reason I’ve never had adequately explained, led The Clash to believe their cab was headed to Polydor where they’d sign with Chris Parry. Parry had produced some early demos & they’d established a rapport. Bernie hadn’t bothered to tell the band they’d been rejected outright by Parry’s bosses. (Parry would go on to sign The Jam, Siouxsie, The Cure, etc.)

So it was a big surprise when instead The Clash pulled up to CBS Records’ HQ. There they were met by Chairman Maurice Oberstein who presented them with a £100,000 contract which they duly signed. The ink was barely dry before the cries of “Sellouts!” started. On paper it was the most lucrative contract signed yet by any UK punk band. But the terms Rhodes “negotiated” were objectively horrible.

While Joe, Mick & Paul understood the contract as being for 5 albums, a careful reading showed it demanded 13 albums. (Part of the reasoning behind ‘Sandanista¡’ being a triple LP was some stoned attempt to more quickly fulfill the 13 album term of their contract - the boys in legal said, “Not so fast.”). The Clash were also contractually obligated to fund their own recordings, mixes, artwork, tours, and promotion leaving them skint & in debt to CBS until ‘Combat Rock’ finally broke them & a year or two later had them break even.

The Clash didn’t help themselves by further reducing royalties (‘LC’) or forfeiting the 1st 200,000 sales royalties (‘S¡’) of what is widely accepted as fact an already sub-industry standard royalty rate to keep ‘London Calling’ & Sandanista¡’ both priced as single LPs. That made everything so much worse. But at the time of the original onerous contract’s signinv, its architect, Bernie Rhodes, seemed far more focused on getting the most for his 20% off the top than doing the best by his charges.

I’ll skip my extended detailed rant re: Good Bernie vs. Bad Bernie. Short version: Lyrically & presentationally The Clash wouldn’t have been a very compelling band without Rhodes’ early guiding hand. But they overpaid for his services in every possible way. As the band’s confidence grew, Bernie increasingly became difficult & disruptive. On his second tour of duty as The Clash’s manager, Rhodes demanded Joe fire Mick effectively ending the band. Not for nothing his other management clients, The Specials, kicked off their debut single “Gangsters” with the phrase “Bernie Rhodes knows! Don’t argue!”