My SXSW

Finding my way over the decades under the brilliant blue skies of early spring in Austin, TX.

The recent news that South by Southwest (SXSW), the music, media, and tech conference in Austin, TX, is cutting back its music programming next year got me thinking about all that SXSW has meant to me over the years. We’re told SXSW will continue in 2026 without the final music weekend as the City of Austin refurbishes its convention center. Still, I haven’t been since 2019, and year after year since the Pandemic I can’t really come up with many good reasons to spend the time or money. For a lot of years in the 2000s and early 2010s SXSW was unmissable, essential, integral to my job. I really miss what it used to be - or rather, what it used to be for me - something I tried hard to never miss, a week of maximum fun and productivity.

I attended my first South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in March 1990. From its inception in 1987, SXSW has been a festival and music business conference, among other things. the “conference” part meant nothing to me. My band Blake Babies came to play a gig at the famous Ritz Theater on East 6th Street. We weren’t really excited to be there; it wasn’t our choice.

The year before we’d signed to Mammoth Records, a scrappy, ambitious independent label based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, founded by a recent Duke MBA who had recently interned for Eagles manager Irving Azoff, then head of MCA Records. Our debut album, Earwig, had been out since late fall 1989, garnering good reviews and adds at college radio stations around the country. It was exciting to get noticed, but we were struggling on the road without much money or even a functioning tour van.

Mammoth made no secret of its desire to sell our contract to a major label. No secret, that is, once we were under contract. Every New York show became a label showcase, and they tried to get us in front of labels at every opportunity, to our constant irritation and stress. It’s something they’d pulled off the previous year with their first big signing, the Arizona roots band The Sidewinders, whose contract had been sold to RCA Records.

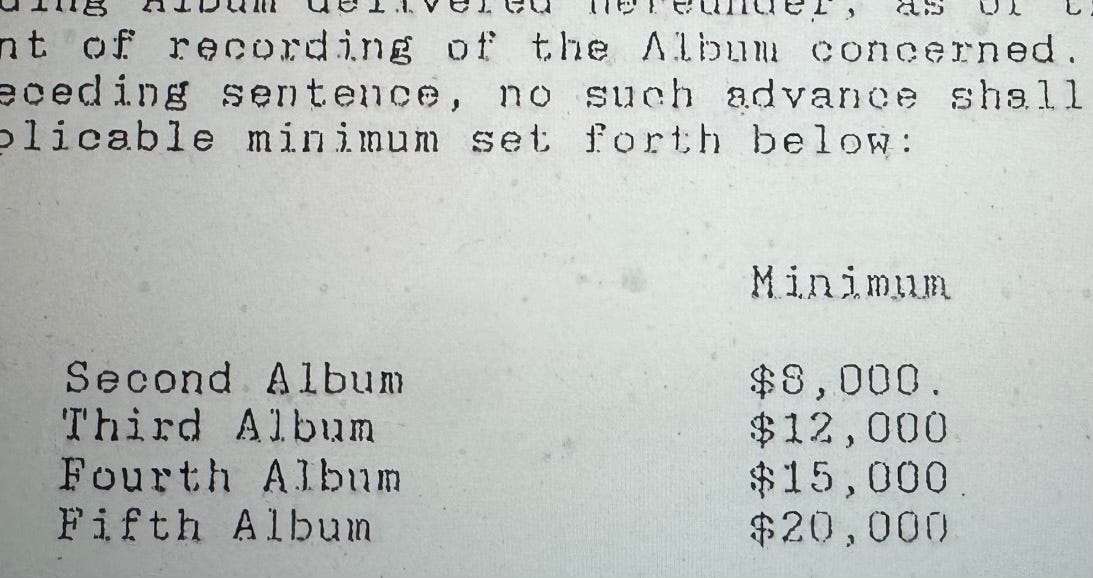

It isn’t that we’re completely against being upstreamed to a major label; it’s that our contract only required Mammoth to pay us $8,000 for the first option album. That meant the big major label advance would go to Mammoth, not us. At least that’s what we believed to be true, though we didn’t have any manager or competent lawyer to talk us through it - we just had our own anxiety and what we heard from other bands. Clearly selling our contract was Mammoths’ business model - that wasn’t a secret. It’s something we hadn’t understood at all when we signed our independent deal, but we found out after meeting the disgruntled Sidewinders, who let us know it wasn’t great for them. Who knows, but we assumed the worst and it made us paranoid about the whole major label showcase thing, and all the people we were supposed to be nice to.

We spent much of the previous year on tour under unpleasant conditions, sleeping on floors, getting on each other’s nerves, struggling to keep our rent paid back in Boston. We didn’t want to go all the way to Texas - an expensive trip - for just one show that only served the label’s interests. We understood that every penny spent on the trip would be recoupable against our future royalties: the flights, hotels, meals, etc. We weren’t given a choice, and that made it feel like a chore for someone else’s benefit.

We had to share a backline with a band called Tiny Lights, who generously offered to lend us their backline for the double bill. Nothing against the charming Tiny Lights from Hoboken, NJ, who were very supportive and generous with us. We were a brand-new touring band that only knew how to sound like ourselves with our own gear - especially me, always obsessed with my gear and guitar tone. We felt uncomfortable and I’m sure it showed (though people have told me over the years how much they enjoyed the set, go figure). As with all of our label showcases around that time, we underwhelmed the industry crowd, and no contract buyout materialized. All that came out of it was thousands of dollars of recoupable costs including the bar tab to entertain industry bigwigs at the venue. Technically, our contract is probably still unrecouped. Label accounting from that era is laughable. Maybe the unrecouped balance means Mammoth paid their own damn bar tab after all. I assume we got some “free” drinks on our tab as well. Welcome to the music biz.

It’s not that we were oblivious to the vibe or the seriousness of the event - Austin had long been on my radar as a cool music scene. One of my hometown friends had been in Slacker, Richard Linklater’s debut film about Austin scene people and I’d watched it several times. Some of my high school buddies moved there in the mid-80s to take their shot. They played on the local scene and the bandleader, a Cuban guitarist who adopted the name Frankie Camaro, had a Grammy nomination in 1985 for playing on an album called Trash, Twang, and Thunder, a Texas guitar showcase. It seemed cool enough to look into the University of Texas as a college option. That’s right, I wanted to go to a college where I could start a band. Berklee was the right choice, but every school I applied to was in a cool music scene. In that sense, we were thrilled to play Austin.

Despite tension with the label’s efforts to sell our contract, I’d developed a friendship that continues to this day with the label manager, Steve Balcom - the guy who actually signed us and fought for us day to day. Whereas the Azoff guy wanted a cash-out (which he eventually got, another story), Balcom was our friend and advocate, someone we could trust. Walking around the modest festival with Balcom, dipping into the small industry conference at the Hyatt and seeing it through his eyes, it seemed like fun. Despite - or maybe due to - my frustration with the label and my early lessons in the School of Hard Knocks, I was emerging as a student of the industry. Our band’s business and decision-making increasingly fell to me, and I eventually became obsessed.

As I played SXSW most years from 1990 through 1997 with different bands and solo, I took time to learn as much as I could about the industry. I paid more and more attention to conference side, noting changes from year to year.1 When I released my first solo album on the tiny Indiana independent Flat Earth after my Mammoth deal ended, I talked the label into getting me a conference badge so I could help them network. I had no idea what I was doing, but I passed out a lot of CD samplers and made a few lasting friendships. Back then, people wanted to help.

I took a few years off SXSW in the late 90s as I began to transition out of full-time music by finishing my undergrad degree with an eye towards law school. I returned in 2001 when Blake Babies reunited and signed to Rounder Records. That’s right - I was a Rounder artist 16 years before I became the label’s President. We did a run of dates that spring, including a stop at SXSW to play the Rounder showcase. That was soon after Heather and I got married, and the tour itinerary showed two full days in Austin. “Great,” I thought. “We can take a nice day off and hear some music.” Not so fast.

In the few years I’d stayed at home, the festival seemed to explode in scale and scope. I’d attended a few day parties on South Congress, but the day party options seemed to increase exponentially. Our updated itinerary revealed five performances, three of them on our expected day off, including a plumb instore at the legendary Waterloo Records. We worked the entire time, wheeling amps down the street and loading drums up some rickety fire escape. It’s expected now, but at the time it seemed completely insane.

By the time I started attending the conference as a baby lawyer aspiring to work in music a few years later, I’d already been to play nearly ten times. Back then, SXSW had a continuing legal education (CLE) program. Law firms sometimes provide a CLE budget for their lawyers to attend a conference relevant to their practice. For those first few years I was lucky to get approved to attend a music law conference. I didn’t yet make any money as a music lawyer; it was an aspiration. It was also incredibly valuable, and I hung on every word of the CLE. I needed the education so badly as I had my first opportunities to actually represent clients in the music space. If anyone responsible for approving my CLE budget during those years, I am deeply grateful. Thank you for indulging my folly, before it showed any real signs of becoming my actual business.

Sure, it was a hell of an education; but so much fun, more fun each year as my law practice and network grew. After all the struggle I’d endured as a musician, now I could have my own nice hotel room and a conference badge I’d gotten for free from being a mentor or sitting on a panel, or eventually moderating panels I designed. To see the festival from the other side was quite a revelation. Playing SXSW, artists will confirm, mostly sucks. It’s inconvenient, exhausting, logistically difficult, and probably not worth it. Attending SXSW - at least in those heady days of the ‘naughts - was a total blast and worth it on every level.

Once I’d begun actually doing these little music deals a couple years into practice, SXSW became the place to meet in person all the people I’d gotten to know on work emails and business calls. In those days, music work comprised maybe 20% of my actual work; most of the time my life didn’t look any different from any Birmingham big-firm transactional lawyer. I went to the office every day in my suit and tie and did my best to bill, bill, bill - mostly on corporate work with no connection to music. Music work was my delicious dessert after a mouthful of dirt as the low man on some massive corporate finance or real estate deal. What a life. I dreamed of the life I have now, literally. SXSW was an intoxicating, at times intoxicated, window into my future.

I used to make time for one indulgence every year, some bucket list, once-in-a-lifetime show. I spent a long evening at a dull Universal Music showcase to catch Amy Winehouse in a small club. I networked to get into a small venue to see Bruce Springsteen one year, no regrets. I was there for Flaming Lips’ 1997 “parking lot experiment” performance of their experimental work Zaireeka. In 2013 I saw The Stooges reunion with my buddy Mike Watt. In 2010 I’d planned around another bucket list showcase, Big Star on Saturday at Antone’s. I’d never gotten to see one of my favorite bands, but then the heartbreaking news broke that leader Alex Chilton passed away on opening Tuesday of SXSW music week. Instead, the surviving members held a tribute, including a gorgeous performance of Nighttime by my friend Evan Dando - the very person who introduced me to Big Star in 1986.

I cherish those musical memories, but by far my most special SXSW moments involved breakouts for the acts I represented or signed. To that end, the peak year - also my professional breakout - came in 2008. That’s the year I had my first artist client, Bon Iver, completely blow up at SXSW. The self-release of For Emma, Forever Ago came out in 2007, but Jagjaguwar had just re-released the album to huge buzz and acclaim. Every show had long lines and packed rooms, every performance absolutely spellbinding.

I learned that having a buzzy client in the middle of a breakout meant you got to see everybody by just staying in the calm center of a music biz hurricane. That became my favorite place as more and more of my clients had breakout moments that sometimes involved actual dealmaking. Every year more acts I worked with had those breakouts, Dawes, The Civil Wars, Alabama Shakes, St. Paul and the Broken Bones, Julien Baker. I had less and less time for the CLE, as I spent more time in the eye of various industry clusters as A&R reps, agents, and managers took their shot. Those are the years I couldn’t skip, often at the expense of my family’s Spring Break trip (though I did sacrifice a couple years to the beach). That’s why we sometimes fashioned SXSW into Spring Break for the kids, annoyed to miss their well-deserved week on the beach. Sure it was selfish to insist on going, but I had so much fun. By Saturday night I’d start to feel that creeping depression of having to return to the office and the stacks of contracts piling up from corporate clients who didn’t care a bit about SXSW or my shadow life as a music dealmaker.

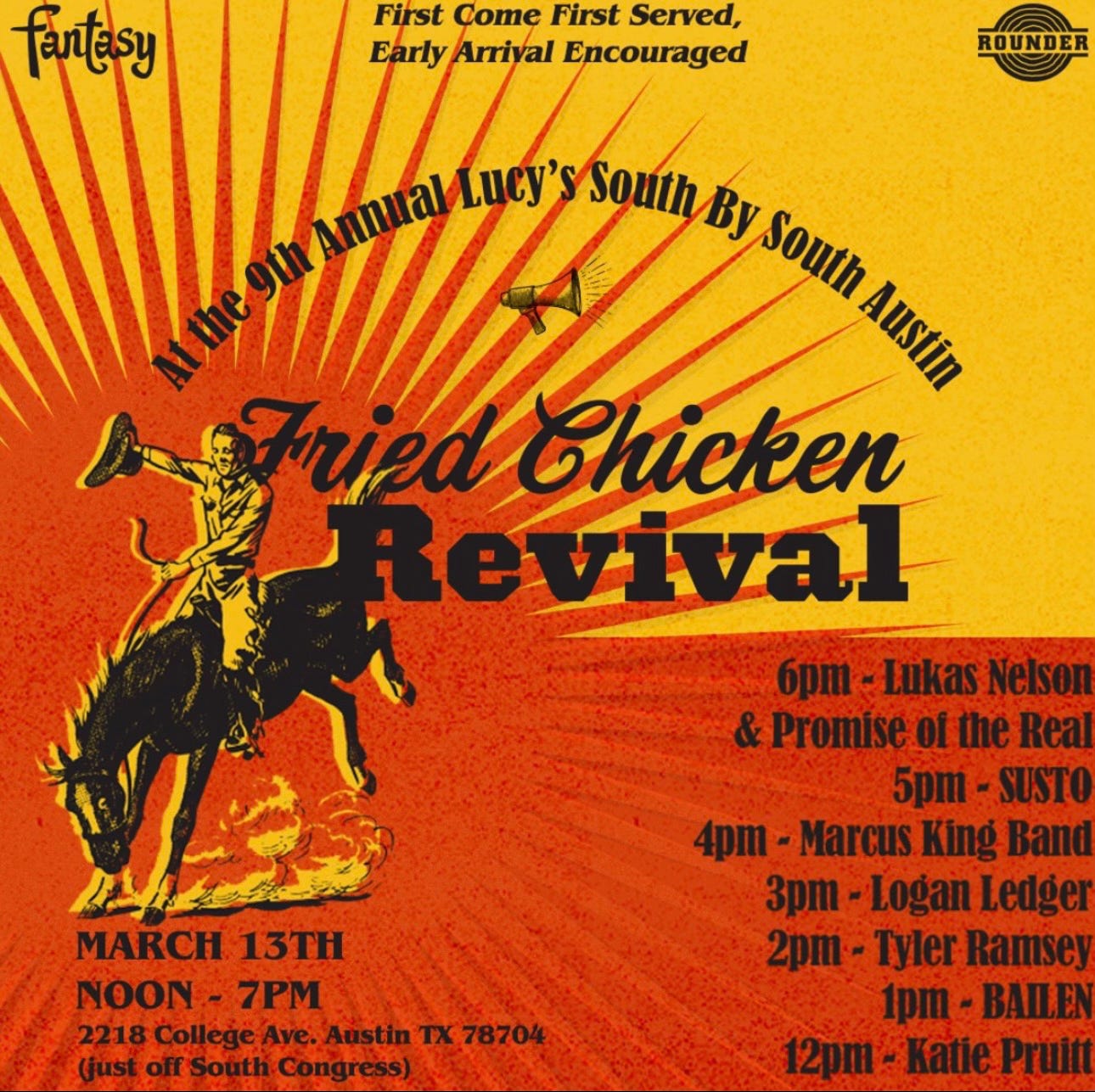

I’ve been back only once since 2016, after which I left law practice for my label job. I can tell you it’s a very different dynamic being on the label side rather than the artist’s team. I had no appetite to chase the flavor of the moment - I knew how futile that could be. My only SXSW visit since then - in 2019 as President of Rounder Records - I collaborated on a day party with our sister label Fantasy Records to put on a day party featuring acts on our labels. I called my buddy Cameron Smith, a music festival insurance agent, who puts on a series of parties on South Congress every year, more for the locals. Our party was actually too successful - headliner Lukas Nelson and Promise of the Real drew thousands to a space meant for hundreds. I served as the emcee of the festival, but things got so chaotic that I couldn’t even get to the stage to introduce Lukas.2

As you can see from the poster, we hadn’t quite yet found our footing yet as a label. The bigger acts at the time were on the most established Fantasy Records. That started to change later in the years. My greatest memory from 2019, really one of my best SXSW memories overall, is that’s the year I made the necessary inroads to sign Billy Strings to Rounder. It’s wild to think about now that he’s a multi-night arena act, but his quartet played a half-full room above Cooper’s, a barbecue restaurant. His nearly hour-long set consisted of just three songs - two from his 2017 debut album, and a version of Little Maggie, an Appalachian folk song popularized by Ralph Stanley. It’s the first time I’d seen Billy live, and it was all there, absolutely jaw-dropping. The audacity to come out with a 30-minute psychedelic jam to open a showcase. It’s one of many times I’ve had to pick my jaw up off the floor after an SXSW performance. To be in a small room like that, knowing it’s one of those well-kept secrets that wouldn’t be secret long. That’s the best.

I’m not really sad about the changes to SXSW, the possible end of such an institution. Those were different times. I have a hard time remembering exactly how many times I’ve attended, it’s around 20. That’s enough, right? I have different conferences to fill that void now, such as the awesome Americanafest in Nashville. I like that I can do it all and still sleep in my own bed, see my family, and get my work done. I have plenty of awesome hangs at festivals and industry events, some of which look and feel like SXSW in the old days. Still, it’s a sad empty feeling to think I’ll never have another day of those 14 hour days racing on foot from one amazing scene to another another, seeing so many friends old and new along the way under that perfect blue sky of early Texas spring. Ahead of the Texas heat, literally and figuratively. I’d like to think I’ll have another one of those someday. If not, I’m grateful for the memories, and the opportunity to find my way through all that chaos. Over all those decades, it’s hard to imagine my life, or the person I’ve become, without those experiences.

More likely, it’s time for me to develop a relationship with one of the great music cities where I’m not just one of those industry douchebags who shows up one week a year. I can count on one hand the non-SXSW times I’ve visited Austin. In the meantime, consider me grateful for all the incredible times.

It must have been around 1995 when everyone started asking each other, “are you online?” I realized that everyone with a job had an email address, and I was behind the curve as a guy without a personal computer. Things have moved quickly ever since.

A little more on this, something that I struggle with. Lukas Nelson is a big star in Austin (and elsewhere), with a lot of committed fans. His most aggressive fans occupied the entire area right in front of the stage, and even though they’d seen me introduce the prior acts, some of these people threatened to beat me up as I tried to push through to the stage. They screamed in my face as I tried to push through. It didn’t really matter in the end; but I planned the party, I had reasons to be there. It’s a free show, nobody had a right to aggressively protect their space like that. I see it on the rail at Billy Strings and Sturgill shows. People need to relax about their entitled ideas at events like these. We all deeply appreciate fans and acknowledge what you bring to the party, but for God’s sake don’t be a dick.

Appreciated, John. We've been crossing paths for years longer then I've known you. Kindred spirits. I worked on the sponsorship program @ sxsw in 2008 & 2009, and interned as early as 2001. Great times over 20 years. Sad to see it and Austin change, but such is how life seems to be going... As I type to you from LA, where I live much of the year nowadays. Hope you & family are well.

I loved the article. I found it interesting that the photo from 2016 showing you with Houndmoiuth among the breakout groups was just a month before Katie did her own breakout. I believe it was the best thing she ever did!