No Part of Nothin'

What is Country Music? And Who Gets To Decide?

The idea for this aritcle came to me over a recent lunch with an LA music executive who is navigating Music Row for the first time as part of the team for fast rising, country-adjacent client. I shared some stories about my integration to the country music community, as he became increasingly agitated, even a little angry. “Nothing has changed in ten years. That’s exactly how it is now.” I partly agree and partly disagree with his assessment, but I’ll get to that. First, the impossible question: What even IS country music in 2023?

My title is in reference to Tyler Childers’ now-legendary acceptance speech for Emerging Artist of the Year at the 2018 Americana Music Awards. In full disclosure, I’m a longtime board member for the Americana Music Association, which hosts the show and facilitates the awards process. I’m a full-on believer in the mission of Americana, namely “to advocate for authentic Roots music from around the world.” Easy. But wait….what even IS authenticity? (That’ll be for another post.)

In the fall of 2018 I was president of the iconic roots music indie label Rounder Records. I’d been a big Tyler fan since 2016 when my law client, fellow Kentuckian Sturgill Simpson brought Tyler’s music to my attention as his producer and early champion. By 2017 I became convinced (based on the quality of his work) that Tyler was a global superstar in the making, so I jumped right in to the fray to try to sign him to a record deal. By mid-2018, however, Tyler had multiple major labels chasing him, having reached the same conclusion about Tyler’s future, assisted by their state-of-the-art research algorithms that measure “consumption” on digital platforms. Something was happening on streaming platforms and social media that signaled a new era. By the time Tyler strode out on that stage I’d seen him live a dozen times; despite my disappointment over losing the beauty contest, he was the most exciting artist in the world to me. Tyler represented the future, which made his words especially sharp.

It was a little disorienting to hear Tyler’s words in the Ryman Auditorium that night. The mood in the room changed quickly as he spoke, but I fully grasped the crucial line: “As a man who identifies as a country music singer, I feel that Americana ain’t no part of nothin’, and I feel it’s a distraction from the issues that we are facing on a bigger level as country music singers.”

Processing, I felt a mix of emotions. On the one hand, I found it a bit upsetting that Tyler stood on that stage and accepted the award with a speech that seemed to disrespect the organization and community. Said community - the actual Big Tent that country likes to claim to be, has had a decades-long run of championing great music that lives in the margins, and often contributing meaningfully to building superstar careers - such as Tyler’s. Americana didn’t break Tyler, and likely it wasn’t there right from the start as he toiled in obscurity for half a decade before he caught any sort of a break. But by the time his music started to connect with a larger audience that existed in the margins of the country mainstream, Americana (particularly as a radio format) was there for it in a way that Country was not.

At the same time, I deeply related to and appreciated his words. I wished he’d managed to emphasize the failures of country over any perceived irrelevance of Americana. That said, who are the “we” that face these bigger level issues? Is it Appalachian singers? Is it “Red Dirt” singers from Texas, or bluegrass traditionalists? Probably, but what about people of color, LGBTQ+, women? Now that Tyler has shown us more of his heart through his work and public profile, I think it’s safe to say it’s all of the above and more. Every country music singer disenfranchised by mainstream country - that alleged “big tent” of old - could be part of the collective “we” in Tyler’s speech. It’s clear to me that parsing Tyler’s words leads to a singular conclusion: He is angry at the Country Music establishment, and he is lashing out because Americana’s inclusiveness is a distraction from Country’s failure.

I’m writing this the day after 2024 Grammy nominations posted, and the changes over 6 years appear encouraging. Tyler has four total nominations, three in Country categories and one Americana. That’s right, there are four “Americana” categories in the Grammys, along with four Country categories. Americana ain’t no part of nothin’ perhaps, but it’s a big part of the Grammys - equal in number of awards to country - and it’s not by accident. Nevertheless, if you ask many Music Row executives and rank & file workers, they will tell you that the Grammys don’t really matter. The CMAs and ACMs are the awards that really mean something in Country. Grammy voters, they’d say, don’t really get country. They aren’t part of the community. On The Row, we have our own awards because the [CMA/ACM] membership understands the music, the community, and the business culture. Sure, a Grammy looks nice in the trophy case; but a CMA Award really means something. Seriously, I’ve heard this so many times. I’ve observed the subtle eye rolls when you mention Country-category Grammy wins for marginal artists. It’s considered mostly irrelevant.

I moved to Nashville in 2011 to join a Music Row law firm because, as a lifelong fan of country music, I wanted to be in the Country business. I grew a modest music clientele over 5 years with a general practice firm in Birmingham, Alabama. I had several fast-rising artist clients, including the wonderful acoustic duo of singer/writers John Paul White and Joy Williams called The Civil Wars. My first day as a Music Row lawyer that fall was just a few weeks before the CMA awards. The Civil Wars had been nominated for the CMA for County Duo of the Year. Sure, the nomination took me (and I assume everyone on the independent team) by surprise. But what a thrill! This legitimately indepenent act1 that made no real effort to break into mainstream country finds a back door to commercial success and receives this sort of validation? Amazing. I felt proud and excited for the future and for everything I hoped to accomplish in Nashville.

The week of the awards, a colleague took me aside and said, “Don’t listen to what everyone’s saying about The Civil Wars. It’s just bullsh*t.” Taken aback, I replied, “What are they saying, exactly?” “Well,” she said, “They’re saying they don’t deserve the nomination.” A little stunned, I asked why they didn’t deserve it. She said it’s because there are certain things that are expected of Country artists. They’re expected to work songs to country radio, and they’re expected to visit every influential country station to kiss rings, banter on morning drive-time shows, go out late for drinks with programmers, and basically do whatever it took to try to secure airplay. Because, you see, country music isn’t a genre, it’s a radio format. If you’re not on the radio, you don’t exist. If you’re not even trying to get on the radio, then obviously they are not a Country act.

Of course, they lost. They lost to Sugarland, clearly a Country act by my colleague’s definition (see acceptance speech video - “thanks to country radio for playing our songs”). The outrage was over perceived snubs of acts that had played the game and therefore earned a nomination. For me, however, The Civil Wars’ nomination felt like progress. To my ear, they sounded objectively more in a country tradition than, say, Speak Now by Entertainer of the Year winner Taylor Swift (or, for that matter, Sugarland, whose vocalist Jennifer Nettles has pivoted away from country towards classic pop in recent years). In retrospect, Taylor was making a break from the genre in a very deliberate manner, likely slowly phasing out of the style of Country to make a break into pop. Although fans of some of the Entertainer of the Year also-rans pushed back publicly, the critiques didn’t so much focus on the actual sound of her music.

I moved to Nashville to be in the Country business because I’d hit a ceiling working out of Birmingham (TCW hired me in part because they loved my client Bon Iver, and they wanted someone outside “The Row”). Although my own music is mostly rock, I’m a lifelong country fan and student of the history. I love great singing and great songs across most genres, but many of my favorites are country. I learned the hard way that it’s an insider’s industry, and part of being inside for most people means being phyiscally in Nashville. But Music Row is more of a concept, and a process, than a physical place. My mentor at my first Nashville firm told me it would take a few years to plant my feet here. I might as well have put that on my calendar, because he was absolutely right.

I’m a lifelong student of country music history, so I keep in mind certain recurring themes. A big one is the push-pull between “progressive” country and “traditional” country. By progressive, I mean conscious attempts by the business to move the genre into a larger, younger, ostensibly more sophisticated (or at least wealthier) audience. Big crossover successes grow the business, but they sometimes alienate traditional fans of the music. As things evolve to bring country closer to mainstream pop through crossover successes, there’s a natural correction as fans push back and ask the ever-important question, “Is this even country music?”

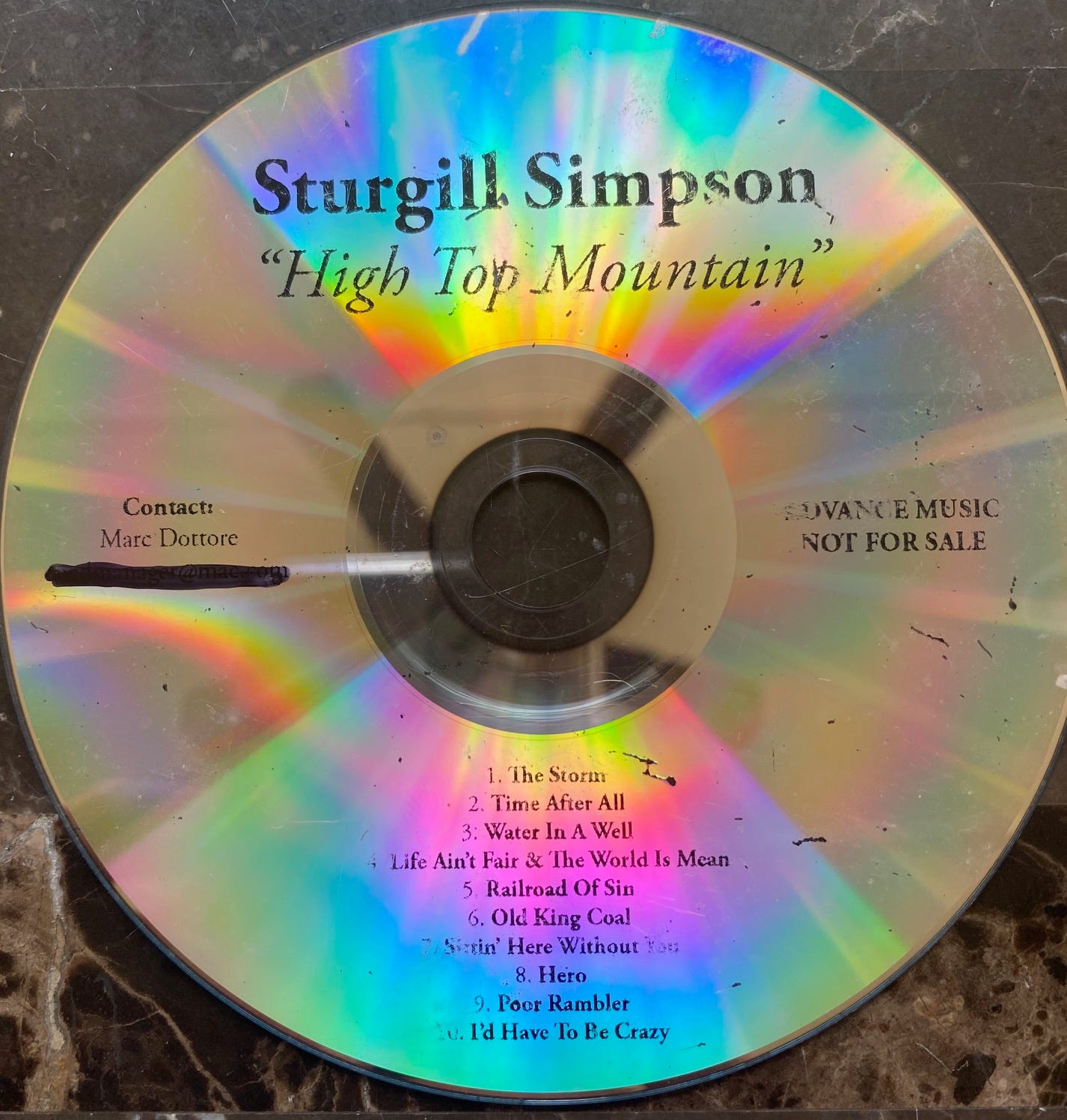

The Bakersfield Sound. Outlaw Country. The New Traditionalists, The Great Credibility Scare. Each of these (and many more) reflected a movement in country that pushed back on the business pandering to crossover success. It’s a sort of market correction that, I believe, has served the important function of keeping things honest to the roots of the music. I had this in mind when I began to work with Sturgill in 2012. I believed that Sturgill’s debut, High Top Mountain is one of the greatest traditional country albums ever made. Remember that its producer, Dave Cobb, was relatively unknown before his pair of breakthrough releases with Sturgill’s first couple albums plus Jason Isbell’s Southeastern in 2013. I believed High Top Mountain could be a pivot point for the industry, just like Ricky Skaggs in the early 80s or Randy Travis a few years later. I believed Sturgill was a generational artist, and I’d tell that to anybody who would listen. But they didn’t listen much, because at that point Sturgill was playing to half-full rooms at best. He didn’t really even have fans yet, let alone a groundswell of industry support. But he had a small core group of industry pros who shared my passion and confidence, and they deserve a lot of credit. But mostly it was the music that found its way, through various versions of word-of-mouth.

I kept a stack of burned High Top Mountain CDs on my desk, and I gave one to every Country industry professional who passed through office. It about shopping a deal; I knew a Music Row deal would have been a disaster. I was just spreading the word, building some buzz. I gave away a box of 30 of these, and I didn’t hear back from anybody. Not one person.

[I found this copy on the floor of my car under the mat years after I’d given the car to my teenage daughter]

When I’d press the issue, and play the music for these executives to ask their opinion, it was always the same predictable stuff. “Yeah, I get it. Sounds like Waylon. But you’ll never get this played on the radio.” “Yeah, this sounds pretty good, but I’m not sure it’s really country. Maybe it’s Americana, or Heritage Country?” If you haven’t heard the album, take a listen. It’s about the most country (sounding) record that’s humanly possible. How can you say it isn’t country with a straight face? He didn’t need to boast about how country he is like the bro’s of the era - it’s obvious. He even overtly says you won’t hear his voice on the radio in the song Life Ain’t Fair & The World Is Mean. We knew this going in - but it’s disorienting to hear these opinions from seemingly intelligent people trying to offer me helpful advice to save me some time knocking on the wrong doors.

In my opinion, we have seen the latest correction, the latest incarnation of that old back to basics theme…but it’s taken a decade to set in. I don’t want to pat myself on the back too hard because I wasn’t alone in this, but I was absolutely right. Sturgill - then Tyler - then others such as Zach Bryan and a great new crop on the way - are the New Traditionalists of our age. However, the reason it’s taken so long to truly impact the Country mainstream is the country establishment, in deference to radio programmers, has fought it the whole way. Radio programmers knew better, knew what the audience wanted, until the audience had a choice and left in droves. Or, more importantly, never adopted radio in the first place because why would you listen to the radio when you have Tik Tok, Instagram, and streaming platforms. That is, if you’re a teenager, which is the most coveted audience when seeking to move country further into the mainstream.

Back to the conversation that inspired this post. Has nothing really changed over a decade and change? Some things haven’t changed much. Music Row remains a closed shop for the most part, and the Music Row process of artist development with a focus on radio is intact. Plenty of Music Row professionals would still reject the idea that Sturgill or Tyler or Zach are Country, though they’d be more careful with their words. But the dirt road that Sturgill and Isbell blazed a decade ago has since been paved, with services and plenty of detours along the way. If I find a great country singer/songwriter with a strong point of view, I don’t have to worry about how the Music Row process will change or demoralize the artist. That process is great for some artists, but it’s poison for others - especially my favorite kind of trailblazing artists who have earned the right to do it their way, and have the audience to show for it. It’s optional, as it should be, because if you can’t crash the gates that are guarded by the Music Row powers that be, there are other gates to crash.

The Country business has been increasingly optimized for decades to produce massive superstars who are able to cross over to become global mainstream entertainers, and the singular point of entry has been country radio. But not every country singer wants to be a global superstar regardless of the creative cost. Most artists I’ve known who have scaled the heights of mainstream success (and many who haven’t, or haven’t yet) would rather remain obscure than become a household name on the back of work that isn’t truly their own, or work they aren’t proud of. These days the truly great artists like Tyler can do it on their terms right from the start, without compromise, and even while being on a major label. Even if I’m disappointed we couldn’t make a deal for Rounder, I must admit that Tyler has seemingly done just fine on a major label. And RCA Records has done well with Tyler. They’ve allowed him to be his authentic self in every way, and it’s worked. He let his audience know in a recent New York Times interview that his career has a shelf life by design, as he plans to drastically limit and then completely end his output. To my knowledge, RCA Records is on board. I don’t think that would have happened 20 or even 10 years ago. The industry is better than it was, in large part, because someone Tyler can be massively popular without compromise and do exactly what he wants and nothing more, as a country artist. And he can do that even if country radio doesn’t exist - or if Tyler Childers doesn’t exist as far as Country radio is concerned.

I say legitimately indie as opposed to independent labels, such as Big Machine and Broken Bow, that function as a part of the Music Row establishment. “Legitimately Indie” to me means the label is a small, independently distributed mom & pop operation with no direct connection to the major business.

'He is angry at the country music establishment, and Americana’s inclusiveness is a distraction from Country’s failure' - such a GREAT takeaway from this speech - it is one I have reflected on regularly, and have had mixed feelings about - and I just love how you framed it here. Thanks for your writing!

Bottom line for me as a country fan, all niche-genre weed-picking aside, is that for decades, whether you loved it/hated it/were indifferent to it, if you heard a country song while walking through the grocery store/pharmacy/wherever, you didn't have to turn to anyone and ask, what kind of bizarre form of music is this? Of course, it was country music. It was country when it was the Carter Family & Jimmie Rodgers, it was country when it was Johnny Cash & George Jones, it was country when it was Alabama and Ronnie Milsap. Obviously there was some sonic evolution along the way, but it didn't make the music unrecognizable. One could be forgiven for watching the parade of face-tatted dudes in t-shirts rapping in autotune about their tractors these days being called "country" and wondering if the entire genre has lost its rabbit-ass mind.

I can't help but wonder if the Uncle Tupelo's and Jayhawks of yesteryear that were relegated to the no-depression/alt-country bin wouldn't have seen more fruits from their labor if Americana were as entrenched in the industry in their day as it is now.