The oldest of our three kids, Anna, is leaving the nest next month. She’s finished a Masters degree, has her first real job, and she’s moving into her first post-college apartment. She’s only 22. It’s been remarkable to watch how effortlessly she has checked off her list of goals. She talks openly about how she plans to decorate her first house and when she thinks she’ll get married and start her own family. On every level, she seems so different from me at that age.

I knew from an early age I wanted a creative life. I knew I wanted it before I had the words to describe it, I wanted to make cool shit. That’s partly because I’ve always been drawn to creative pursuits like drawing and music-making. It’s also because I intuited from an early age that I wasn’t cut out for the straight world.

I always struggled to see myself doing normal grown-up stuff. I saw myself as exceptional, or incompetent, or both at once - exceptionally incompetent. In contrast, our kids have been enthusiastic about a conventional path: going to a big college, getting a great job, making good money, having their own family, and living their version of the American dream, similar to the Norman Rockwell ideal. I saw myself as rejecting all of that in favor of…I don’t know, chaos?

In fact, if someone gave me the choice of having a stable, well-paid job in a creative field or my band signing to Homestead Records, I’d have chosen the fly-by-night record deal in a heartbeat. I wanted to be in that club, to experience adventure in the rock underground. I didn’t really care about making a living, as long as I didn’t starve or end up homeless. I accepted sleeping on floors and scraping by as part of the experience I chased.

As a little kid, I used to daydream constantly. Spinning elaborate fantasies became my happy place. I created these elaborate scenarios, places I liked to go in my mind: complex stories with me as the hero, a rock star but maybe a war hero or athlete. I was pretty isolated at times, and I usually preferred my fantasy life to my day-to-day reality.

I started having trouble with school around the time my parents separated, third grade. It’s also the year my best friend Eric moved away. Eric and I had been inseparable from age 4, so much that I hadn’t really bothered to make any other close friends. Eric and I created fantastical worlds together, then suddenly I had nobody to share it with. That’s when I withdrew. I held a lot inside, which I believe led to some self-destructive habits.

I started turning in half-finished homework assignments, mentally giving up in exhaustion before I could complete the task. I knew what I was doing and I knew there’d be consequences, but completing a task felt so hard, nearly impossible. I struggled to fill in half a worksheet, or the first page of a quiz. Then I’d give up and drop it in the box, hoping it might go unnoticed.

Third grade is also the year I discovered Kiss, which became my obsession. Eric and I didn’t talk about music. I made new friends who shared my enthusiasm for Kiss, the fellow screw-ups. I spent a lot of time drawing pictures of Kiss concerts. I’d never seen a Kiss concert or even a video of them performing, but I collected photos from music and teen magazines that I pasted into collages. And I drew lots of pictures of Kiss as I daydreamed about going to their concert…or being one of the people onstage. I worked hard on those drawings, as the process fueled my daydreaming. My dad thought maybe I could develop a talent for drawing and become a cartoonist or illustrator. Maybe so, but I wasn’t drawing to get better at drawing. I drew the world I wanted to be part of, which included hard rock bands, martial arts fighters, motorcycle gangs, and burnout hippies. I guess there were some red flags.

That was the year we took our first standardized tests, called the Iowa Test of Basic Skills. I remember sitting at a table with my super smart classmates, kids who went on to Ivy League educations and careers in academia and tech. Back then we were just kids taking a test together, showing off for each other. These kids made a big show of finishing their sheets incredibly quickly and turning their papers over, setting down their pencils. I was only halfway through the questions in the section and I felt embarrassed to be so slow. To avoid embarrassment, I randomly bubbled in the rest of the answers and turned over my test paper. I followed the same strategy for nearly every section. I thought I was so clever until my parents saw those scores.

I wish I’d known at the time that these standardized tests represented such a fork in the road for me. My poor test scores shocked and horrified my parents. They couldn’t believe it. My folks are University people, having spent their entire lives in and around the Ivory Tower, most of their greatest accomplishments measured in academic accolades at the highest level. My older brother was a straight-A student. I doubt my parents ever considered that they’d have a kid who struggled through public school in Indiana. Such a low bar! That’s when I started to give up on the whole idea of doing well in school.

With my lousy grades and scores, I wasn’t chosen for gifted and talented programs, advanced reading groups, or much academic encouragement. That is, other than the threats, warnings, and desperate pleas from my parents as I brought home one poor report card after another. I struggled to do the work, fell behind, then struggled through anxiety about my parents’ impending freakout. I worried about it so much I developed insomnia, but I never actually made the effort. It’s a cycle that repeated every nine week grading period from grade school into high school. I was grounded for poor grades for nearly all of middle school. I can’t imagine why I never made up my mind to just push through and do the work. I can only assume that actually doing the work wasn’t an option. I struggle to understand this period of my life, why I couldn’t just do the work.

Unlike my own kids who thrived in middle school, I suffered through those years. The one bright light in my life was drumming. I played drums in school band, and in seventh grade my parents got me my first drum set. I was still living in fantasyland, but now I could channelled it all into drumming. I came home from school and went straight to the basement, where I’d play for hours. I played entire concerts before rapturous audiences, huge crowds that included all the popular girls in front, vying to catch my eye. My practice was mostly undisciplined. As I got into lessons and found a little more focus, eventually I got legitimately good at it.

Since I’d given up on school and didn’t see much hope in any other future, I went all-in on the drums. It’s the first time I worked hard at something. I’d never been particularly good at sports, mostly due to lack of effort. I’d established I wasn’t good at school. But with drums, I felt, I could be the best - or at least the best in my school. I could make something of myself if I put in the time, which excited and motivated me. By high school, playing drums and being in a band became my identity, overlapping with my emerging identity as a punk rocker. Miraculously, as my social life took off, my grades improved. I wanted my freedom badly enough to bring home good enough grades so that I could keep doing the things I enjoyed.

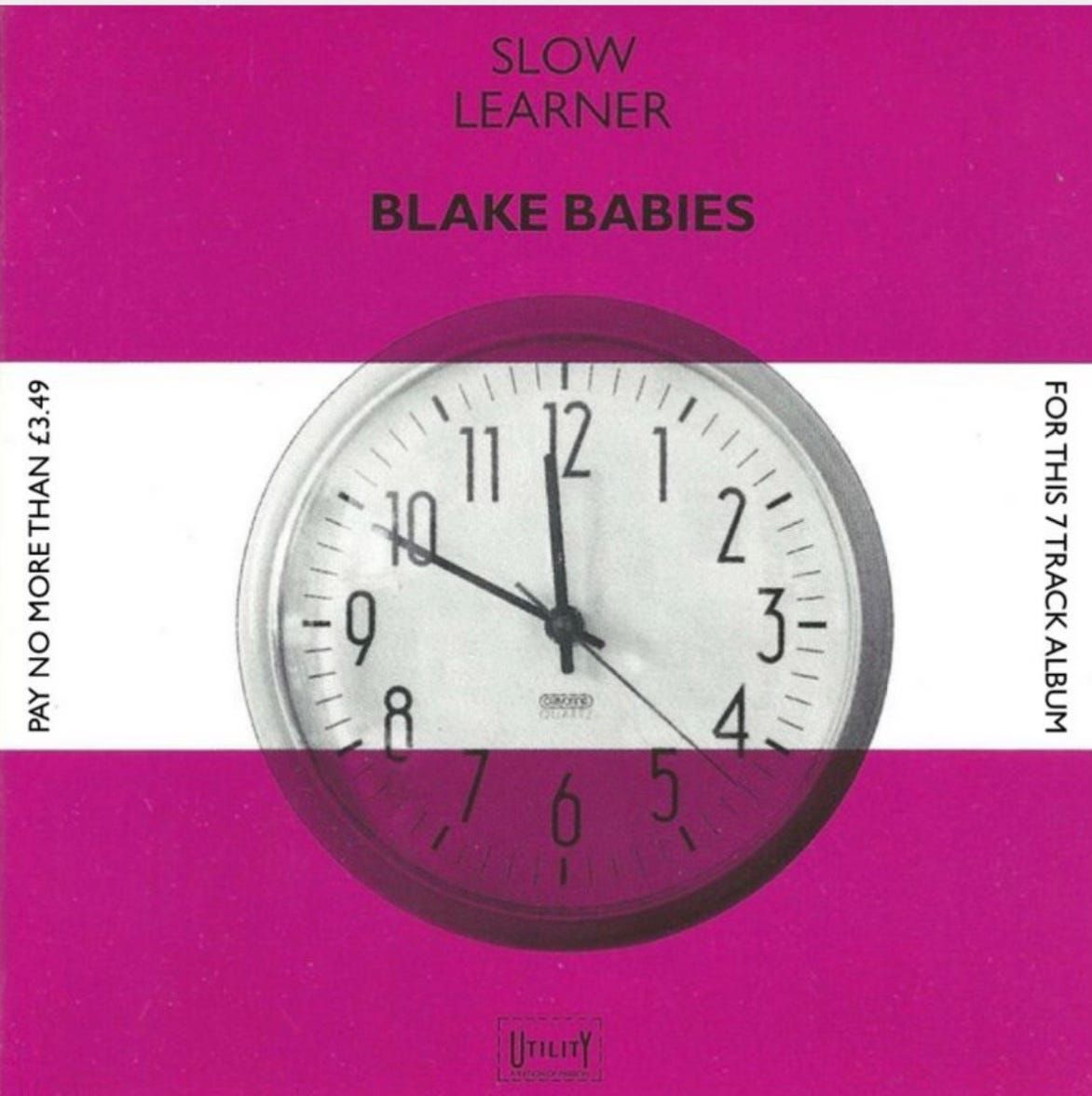

By the time I started playing public gigs in early high school, my drumming opened doors. I got invited to play in good bands with older guys, and I developed a good reputation around town as a musician. Then in 10th grade I achieved my highest goal of all by getting a girlfriend, Freda (yes, from Blake Babies). Suddenly, every door flew open. In many ways, that’s when my life started. That’s when my future started to take shape and I became the person I’ve been ever since.

Something incredible happened around then that I barely noticed at the time. My focus shifted from some fantastical imagined future that would never come to pass to the present day reality and things I could actually accomplish. I didn’t need to fantasize because I didn’t need to escape any more. Musical skills and other interests I shared with my new friends opened the door to a community of people just like me, screwups and outcasts who were actually super smart and ambitious. Their acceptance gave me confidence and influence. My standing in the community opened the door for me to get this amazing girlfriend and a bunch of cool buddies, many of whom I’m still in touch with today. All I craved was more freedom to keep growing and building towards the epic reality I imagined.

I didn’t have much ambition or work ethic as a little kid, but I found those things through my punk friends. Once we all came together around common purposes, with hardcore as the glue, we all became very ambitious. We became collectively ambitious. We avoided the crushing boredom of pre-Internet life by creating our own opportunities: booking regional gigs, figuring out how to record and release our own music, making fanzines, building our own halfpipe, and even inventing our own all-ages club to play and book our favorite touring bands. It took a lot of creativity and effort just to get beer on the weekends. We were an effective and enterprising bunch, making our own wishes come true by creating our own scene.

Today, most adults would describe those kids as ambitious and entrepreneurial. We’d write about it in our college applications and our parents would brag about it on Facebook. Nevertheless, to our parents, teachers, and all the adults at the time, we were just high-risk kids doing high-risk things that didn’t - and probably wouldn’t - accomplish anything substantial or of lasting value. I knew they were wrong, though “making something of my life” to me didn’t mean making money, having a family, or owning a home, or all that conventional stuff. It meant getting my band launched, period. Everything else could follow that goal. I found my focus, but my laser focus was on an ambition that neither led to wealth nor status outside a very small community. I couldn’t have cared less. By the time I moved to Boston to go to music school at 18, I had a single-track mission.

I’ve learned over the years to push through adversity and (usually) to complete the tasks I’m responsible for. I do hard things on purpose because they’re rewarding. Simply put, I’ve become a different person. I have no resentment towards my parents. I recognize their frustration with me came from a place of great love and concern, of wanting me to have a decent life. To them, I was throwing it all away for nothing, destroying any possible future. I know it was disorienting for them 20 years later when I graduated top 5% in law school. I always had it in me, why couldn’t they find a way to motivate me? I don’t know, but I know I had to find it on my own.

I guess I’m not really different from my kids after all. I just came up in a different time, with different challenges, slow to launch. Today if I presented like that I’d be referred to a therapist. They’d prescribe me some amphetamines and send me back to class fully zombified. I’d be a couple inches shorter and otherwise no better off. All us Gen-X’ers had to raw dog our way through our various colors of neurodivergence, with only our active imaginations and 60s sitcom reruns to comfort us. Eventually, I figured out how to power through unpleasant tasks in a way I find satisfying, but nobody handed us the tools to solve that problem. I have empathy for that younger version of me because those years - especially middle school - truly sucked.

I assume the shift from magical fantasy to practical (and often magical) reality was just part of growing up. I invented all those fantasy worlds because I hadn’t found my identity. It was a big part of forming my identity, the seedbed of my creative life. Once I found it and manifested in a music scene, I no longer needed the comfort of a fantasy life. Nevertheless, it was all necessary for my development. I developed a powerful imagination, big enough to invent entire private worlds. Now when I create, I’m tapping back into that deep well of made up stuff, making up new stuff.

I used to believe everyone struggled through middle school because everyone I knew struggled through middle school. Then I met my wife and we had our kids, everyone did just fine in middle school. I suspect that most creative people struggled to find their place in mainstream culture and had to reinvent themselves through their own imagination. Maybe that’s what defines us as creative people. Rather than wishing my kids followed a similar path, I should be grateful they haven’t had to struggle so much to find their path. But for me, I’m grateful for the struggle.

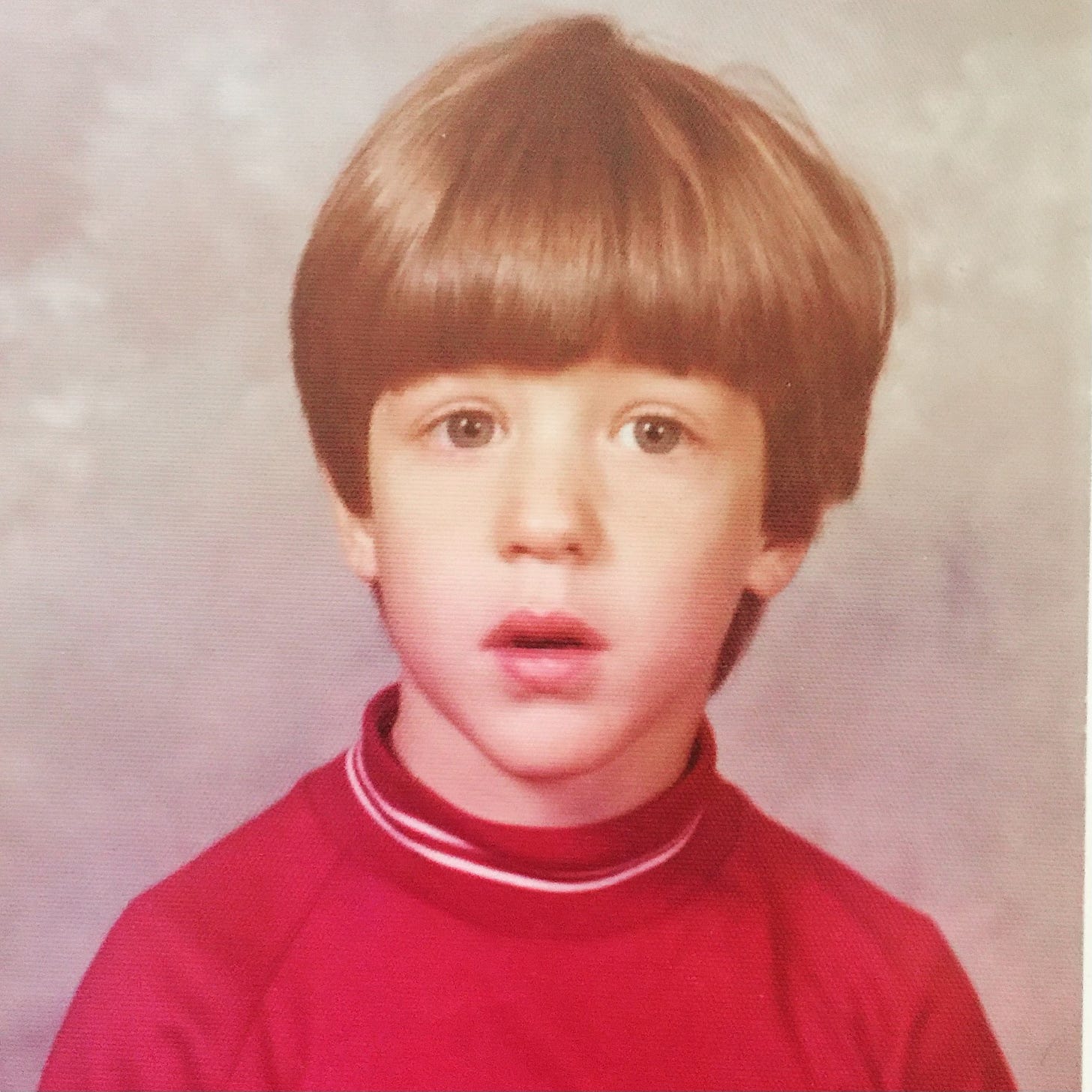

Oh my God. That photograph of you. The look says “please don’t hurt me!”

i 'enjoyed' reading this! well-expressed, and in many ways very similar to what i was thinking growing up and different in some ways. but, we ended up at the same 'place', ha ha. and, yeah, no regrets. thanks for this, xxxcm