The Bidding War

A One In Ten Chance of Rock Stardom

It’s wild how much the music business has changed since I started over 30 years ago. Today it’s mostly about access and consumption, which means the Sea Change has pushed our little boat out to that distant shore that wasn’t really even in our scopes for most of the 90s. Before the evolution of the Internet, before mobile, the CD ruled. you had to buy a pricey physical good to listen on demand. The cost and the infrastructure needed to move and sell quantities of physical goods generally meant you needed a record label to reach a large audience. You needed the distribution because small independent distributors were unreliable (and tended to go bankrupt). You needed a big recording budget because before DAWs, recording was expensive. You needed high-powered promotion and publicity because it cost a lot of money to get music on the radio, on television, and in glossy national magazines. Etc. Etc. You needed a lot of spend and a lot of resources.

Independent music thrived, but Indies tended to go into business with major labels once they’d created real demand for their offerings. Sometimes, as in the case of Rounder, labels needed majors just to survive.

My band Blake Babies signed to a small independent label based in Raleigh, NC, called Mammoth Records in 1988. By the time we began to enjoy modest success, Mammoth’s leadership let us know that they wanted to either sell our contract to a major label (which they could have done without our consent), or else sell the entire company to a major, which they eventually did. We didn’t have management or any sort of business parenting at the time (1990), so we happily went along with the wining and dining from a litany of major label A&R dudes (all guys of course). We enjoyed some nice lunches in fancy LA restaurants, but ultimately we decided to break up. Our singer and bassist, Juliana Hatfield, entered into a solo joint venture deal with Mammoth and Atlantic Records, edging ever closer to a sale. Mammoth optioned me as a “leaving member” a few albums before they sold to Disney’s Hollywood Records in 1997. Things got difficult from there, since hardly anybody left at the label remembered who I was.

During the time of our label meetings I knew very little about the business. I didn’t even know which questions to ask. I learned as I went along as needed as I picked up some of the management slack. I talked to the label and publicist, and I coordinated our radio interviews, got us to the shows and figured out how to collect on our meals and hospitality. I learned from the ground as we navigated in real time. The contracts, however, remained a mystery. I never really read our Mammoth deal, that is until I wanted out. Then I read it with great interest.

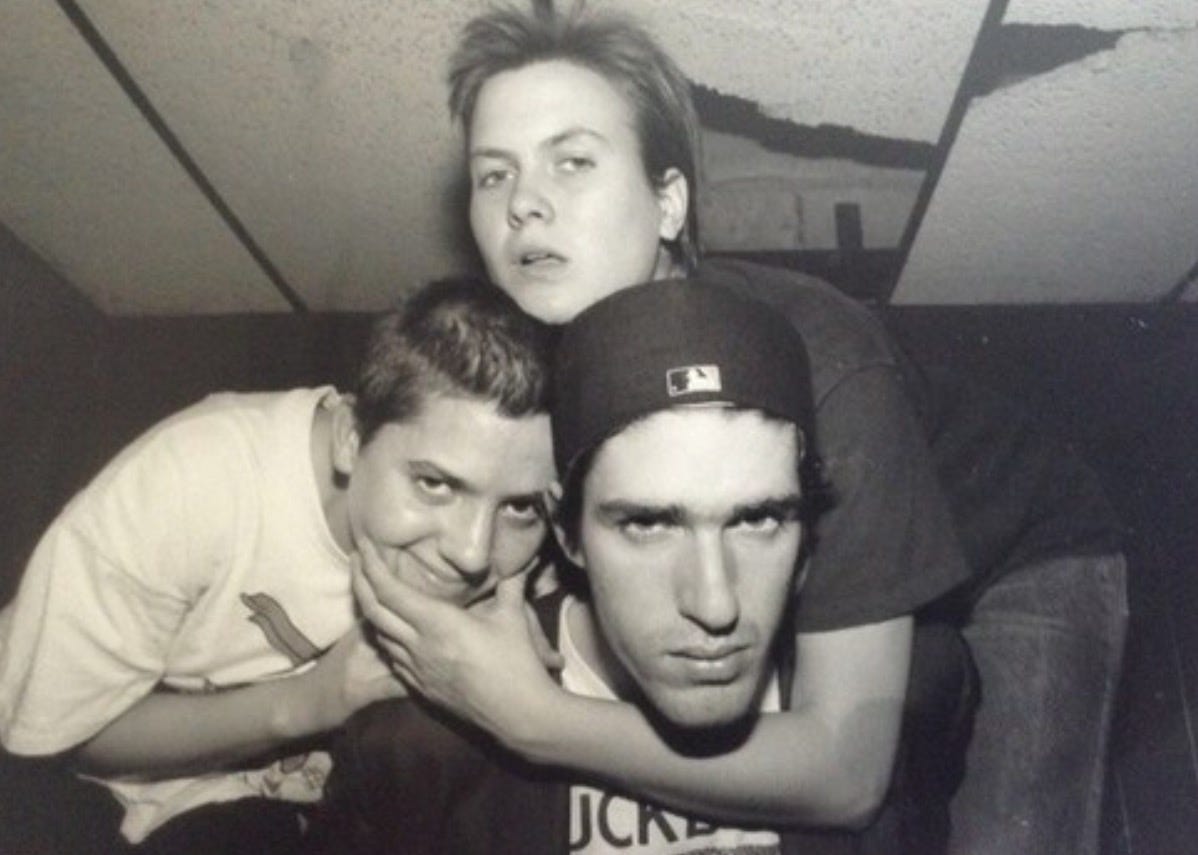

During the difficult period of contract limbo with Mammoth I spent a lot of time collaborating, playing, and just hanging out with my best friend Ed Ackerson. I’ve recently eulogized Ed, who passed away in 2019; so if you don’t know his work I recommend you go down that rabbit hole. In between my touring commitments as the guitarist for The Lemonheads in 1994-5, I spent time with Ed in both Bloomington (where I lived) and Minneapolis (Ed’s home town) to bring his Polara project to life. I joined Ed in a Minneapolis studio and helped him create the debut Polara album, which came out on iconic Minneapolis indie Twin Tone in 1995 to glowing reviews and modest, indie-level success. (You should listen to this album front to back, because it’s one of the things I’m most proud of having help create)

And then things got weird. But first, a little background on how things changed in the rock music business between my major label courtship experiences in 1990 and the weirdness of 1995. In the late 80s into 1990, underground rock music - the music we’d soon call “alternative” but what was then “modern rock” or “college rock” - had mainstream potential but not much actual mainstream success. A few acts - R.E.M., U2, The Bangles - started out as underground but eventually broke mainstream. Other underground acts such as Sonic Youth and Pixies threatened to break out. For an act like Blake Babies, however, a clear path to mainstream success hadn’t been blazed. Record company guys always focused on how we could change our sound to accommodate the mainstream. In retrospect, that’s one of the things that killed our band. With a litany of “experts” whispering in our singer’s ear that she couldn’t make it with a band like us, a poisonous seed had been planted.

Then grunge happened, and by 1995 “alternative rock” had not only been given a name for convenient marketing, but it was metastasizing into a hit-driven commercial radio format. Polara caught the ass-end of the post-Nirvana signing frenzy, when labels would spend millions to sign a nearly-unknown act out of fear of missing out on the Next Big Rock Act. The dirty secret, however, was that most of the acts that got signed in these sorts of frenzies never actually had real success. Many albums got shelved. Many more albums came out with little or no promotion. If I have a chip on my shoulder about the major industry, it’s because I’ve known SO many musicians who let themselves get excited because they signed to a major label. Some cool A&R guy told them that they had massive support within the label, and they’d stick with it until it broke. But then that cool guy wasn’t there anymore, and you realize you don’t really know anybody else there, and nobody will take your call. For a creative musician, that is truly heartbreaking, and it’s way too common.

The feeding frenzy and eventual bidding war for Polara took place over 6 months in 1995-6, a time when it became increasingly clear that my own career was stalled, if I’d ever really had one. You’d think I’d feel pangs of jealousy over all of this happening for my best friend. But I swear I felt only pride and excitement, not just for my friend but for myself. Ed worked so hard for so long to get to this point, but he always made sure I felt part of it. During that time we talked about it pretty much every day.

I can’t remember exactly how it started. Ed produced an album for a band called Balloon Guy that signed to Warner Brothers. He made some friends there and started getting more connected. Then Blake Babies’ producer Gary Smith, who had pivoted into management (including Juliana), became Polara’s manager. Then New York music lawyer Rosemary Carroll signed on. Gary and Rosemary shopped the music to a variety of labels and got some nibbles. Then suddenly the offers started rolling in, and they got better and better. Famous A&R people flew to Minneapolis, or put Ed up in Beverly Hills. He kept me up to date on the proposed terms, in-pocket advances, firm options, full-stat mechanicals, key man clauses, all of it fascinated me.

Sometimes I forget how I really caught the bug that made me want to become a music lawyer. This was it. When I called Ed a few years later and told him I’d decided to go to law school to become a music lawyer, he said he wished he could do it too. Sure, we were music geeks who liked to talk about guitars and records and microphones and whatnot, but we were also students of the business. And we had a hell of an education getting through that deal.

Eventually Interscope Records won The Bidding War, or Beauty Contest, or whatever it’s called. Then almost as soon as the ink was dry they’d paid out well over a million dollars to sign the band, industry currents changed and the label sort of lost interest. It isn’t a surprise that Polara never “made it” in the music business - chances are you haven’t heard of them.1 And that is really the heartbreaking part of the story. All the excitement of a bidding war led to a goose egg. Labels and publishers flushed millions down the toilet on a band they decided not to prioritize. They moved on, and there was SO MUCH MONEY in the industry that it didn’t really matter. They’d make it up with the next Big Hit. But it mattered to Ed. It mattered to Polara.

What I’ve described happened all the time back then. So much disaapointment. If you want to learn more about how ridiculous the business was in the 90s Rock Boom, I recommend reading Jen Trynin’s excellent All I’m Cracked Up To Be: A Rock n’ Roll Fairy Tale. We all knew that maybe one in ten signed bands would even make any money for the label, let alone for the band. But the musician mindset is That doesn’t matter because I’m gonna draw the high card, because it’s my destiny. It’s a version of insanity. I made over half a dozen albums for labels and I never saw a dime in royalties. You’d front load the advance payments because it’s probably all the money you’ll ever see. It isn’t a viable career path at all, but some of us just have to do it. We have to believe. And that makes it all the more painful when it crashes and burns.

Ed landed well after the Interscope debacle. While others I knew who signed huge deals in the 90s blew their money on drugs and other stupid shit, Ed invested in a cool building in Uptown Minneapolis where he set up an incredible recording studio that is still operating today. His studio was his livelihood, and he thrived there. But I witnessed the excitement giving way to profound disappointment. It is absolutely crushing to be treated as the Next Big Thing by big time industry players and then to have them all but forget you exist when it doesn’t go exactly as they hoped.

[Ed at Flowers Studio, 2019]

The Bidding War felt like an alternative reality, but the dream of stardom for Polara didn’t seem out of reach. Remember at the time, I was a member of a big alternative rock band touring the world. We had many friends and peers on the winning side of the equation. But most of the people we knew were struggling, including Ed and me. All we could do was to make the best music we could and HOPE the gatekeepers would take notice.

Today it’s better, if only because it feels more honest. Labels don’t pursue artists until they’re already confirmed commercially viable, based on the consumption data viewed through the lens of a research algorithm. Algorithms are more consistent and less emotional than humans because they just measure consumer behavior. Algorithms don’t have opinions about the art; they have an analytic framework for processing data. But nevertheless, algorithms can be assholes. When the algorithm identifies a safe bet, the offers roll in. The difference now is that when the offers roll in, there’s a viable independent path for the artist. The algorithm’s blessing confirms it! Because in today’s business, you don’t need all the expensive stuff labels have to offer. The Internet kind of leveled the field. You can build it yourself to a point, maybe forever. Eventually, however, labels have the resources to build a modest success into a global hit. By and large, labels don’t sign artists until they believe based on the quantitative data that it can grow into a global smash. Ideally they’re fans of the music as well! But in the end, algorithms rule the day.

Bidding wars like this have been part of my routine for years now, both as a lawyer and a label head. They’re fun for the lawyer because you know it’s going to end up somewhere; but they’re super stressful on the label side because the process is opaque. I’d spend months working on signing an act to Rounder, only to learn after the fact that my offer wasn’t competitive. I don’t miss that feeling, but it feels great when you sign an act that you know is going to connect. Working with artists again, it’s important for me to occasionally reflect on how emotional these times can be. Being a musician is so insecure. But it seems to me a whole lot better when labels are signing artists far enough along to have the option to just walk away. At that point, your chances of making a living are considerably better than one in ten.

But you should listen to their music right now - especially since I spent many hours a few years ago making calls and pressuring low-level Universal Music Group employees to put Polara’s Interscope music on streaming services.

Bangles were top of mind in this piece because their producer, David Kahne, is who tried to sign the band to Columbia. His frame of reference circa 1990? The Bangles. We cut demos with him and he kept telling us which studio musicians he'd want to bring in on the album session (the guy who drummed on the B-52s album, for example). So, basically, telling us to our faces that the band wasn't good enough to make a record.

The change from College Rock -> Alternative Rock was a crazy time to be a "student" of the industry. I still can't believe the amount of cash wasted and the destruction that these fat cats caused on so many talented artists. Then there was the whole "fake-indie" label game the majors played, too. Crazy crazy times. Anyway, a lovely read as I lived it from the outside with other friends having similar situations so I was once-removed too. It was a crash course in how the game was played. It was all part of my education too.