(The) Pixies

If you were part of the Boston 80s rock underground, it's always THE Pixies.

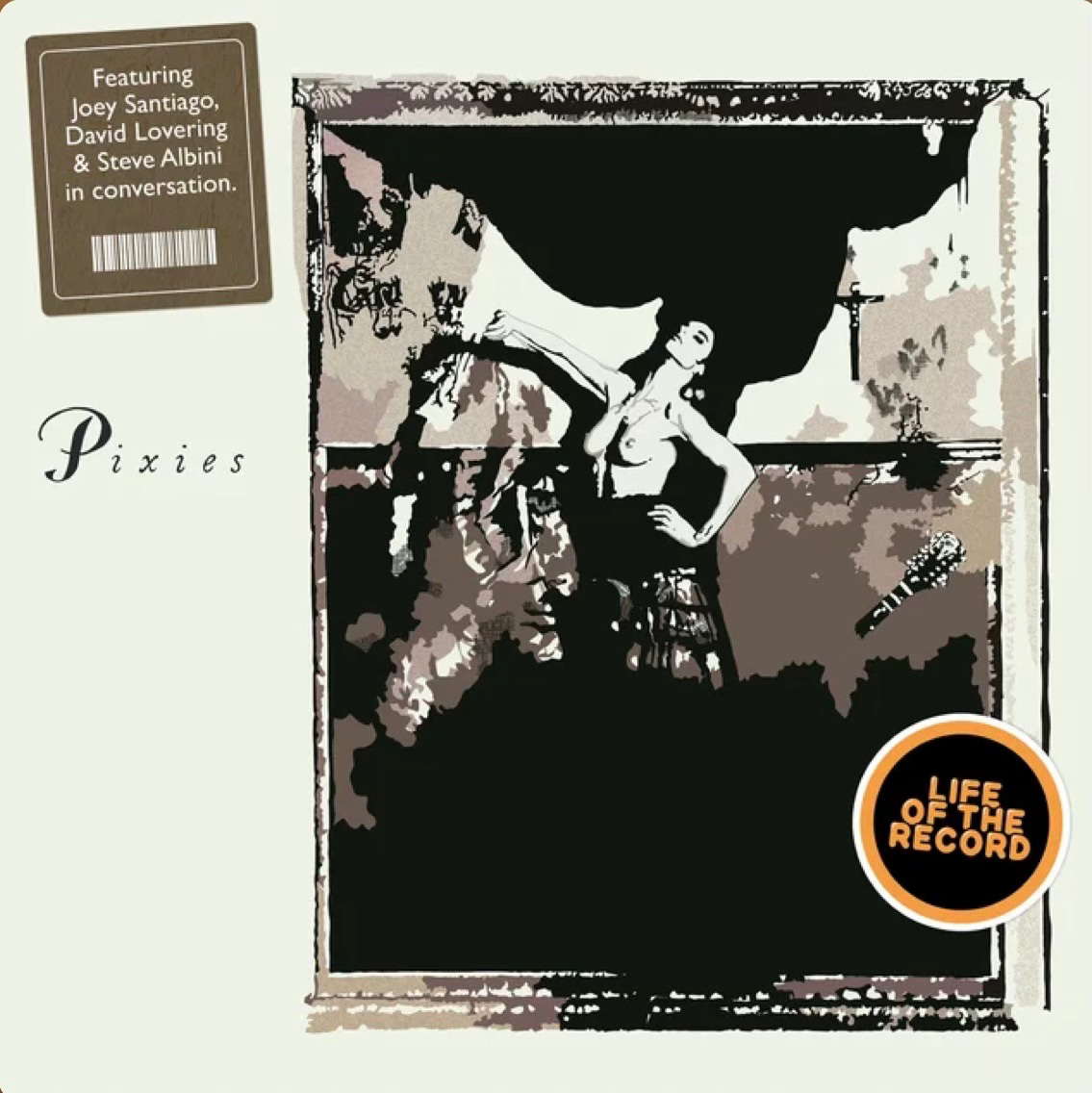

I’ve got a podcast recommendation for you: Life of the Record by Talkhouse. I’ve listened to a few of the podcasts, and they’ve all been good. I binged once already a couple years ago, but I was drawn back in most recently by Ian MacKaye on the making of Minor Threat’s Out Of Step EP - yeah, that’s my shit.

This time I decided to dig a little deeper and check out a few more. It’s been deeply rewarding. There are several of my favorite albums, ones I know intimately. It’s so fun to hear from the people who made the records on how they did it and how they felt about the work. It’s so good - I recommend picking out your favorites and starting there.

The inspiration for my essay came from a conversation about the making of The Pixies’ Surfer Rosa by producer Steve Albini and band members David Lovering and Joey Santiago. I was completely obsessed with Surfer Rosa in its time; it really changed me, re-wired my brain. It was thrilling to be even a close to that explosion of inspiration and infinite creativity. Observing from a safe distance, still close enough to see the tectonic plates of underground rocks start to shift.

1986

I moved to Boston in the fall of 1985 from Indiana, to attend Berklee. We started Blake Babies in the spring of 1986, around the same time Charles Thompson and Joey Santiago dropped out of U Mass Amherst to start their own band in Boston. Legend holds that they took out an ad in the Boston Phoenix in search of a rhythm section. They discouraged technical musicians and claimed Husker Du and Peter Paul and Mary as influences. I know this is true because a late 80s housemate of mine, Claudia Gonson of Magnetic Fields, answered the ad and jammed with them as a potential drummer.

Incredibly, The high school-age Lemonheads and The Pixies played the same audition night at the iconic TT The Bear’s Place in Cambridge in the fall of 1986. I wasn’t there; I didn’t know either band existed. A year later, I joined one and became completely obsessed with the other, an early adopter of an obsession that soon swept the underground music world.

1987

Blake Babies truly came up from the bottom rung in Boston. We came with some privilege - such as having access to the Berklee ensemble rooms, where we were regularly ridiculed by the technical musicians who rejected amateurism. Berklee didn’t help at all in those days: notwithstanding Til Tuesday, there hadn’t been many good rock bands to come out of that place. We didn’t have a community, and we had to figure it out ourselves. That’s really hard, and it makes you competitive. It’s very hard not to constantly compare.

Like The Lemonheads and Pixies, we had to play humiliating audition nights at the local clubs. Those clubs - the Rat, TT’s, probably Bunratty’s and others we didn’t aspire to play, made you pass out tickets to your friends to prove you could draw. I can understand why the clubs did it, and no we didn’t have to sell them. It was a necessary popularity contest. Any band with a bunch of friends can pack a room. We just didn’t have all that many friends before we met the Lemonheads guys. That’s when we started to feel like part of a community.

After we’d played out Wednesday audition night, and done it all over again on a Thursday, The Rat offered us a Saturday night gig opening for a local rock n’ roll trio called Nova Mob.1 We were so excited about our Saturday debut. Then the talent agent called to say he’d made a mistake - that opening set had already been promised to a band called The Pixies. 2

I’m a little embarrassed about what follows. Anyone who has been in a struggling band on a local scene will understand. I felt competitive with this band I’d never heard, annoyed that they got an opportunity that eluded us. I quite arbitrarily decided I didn’t like The Pixies.

Eventually we got our Saturday show, where I think we opened for a local roots-rock act called The Turbines. I was familiar with them, mostly because the bass player from The Turbines occasionally worked the door at The Rat, and he took my fake ID - my brother’s legit ID - a couple months before my 21st birthday. “Get a cop,” he said, “And I’ll give it back.”

That night turned out to be truly magical, one of the greatest nights of our lives, because that’s the first time we met our future producer and mentor, Gary Smith of Fort Apache Studio. After our set he approached us, absolutely beaming, in the filthy, postage-stamp size dressing room and told us straight away that he owned Fort Apache and he wanted to produce our record. Our next record, to be clear. We had just released our debut 12” Nicely Nicely, pressing 1,000 copies, approximately 950 of which were still in boxes in our apartment.

Gary helped us load our gear and drove us to the brand new North Cambridge Fort Apache, which leased its second floor space from Rounder Records at One Camp Street. Fort Apache was named because it started in a rough part of Roxbury. But North Cambridge seemed almost suburban. Gary showed us the studio and gave us samples of his recent production work - a couple demo cassettes by Throwing Muses from Newport, Rhode Island, and The Pixies.

I already loved Throwing Muses, and I listened to their tape til it wore out. I didn’t listen to The Pixies tape right away because, you know, I’d pretty much made up my mind. Then Gary hooked us up with a much more appropriate support slot at The Rat - first of three with The Pixies and Throwing Muses.

I met The Pixies for the first time at soundcheck. It was a weird show for them because Kim Deal (then known as “Mrs. John Murphy”) had to return to Ohio due to a death in the family. Charles, Joey, and David played as a trio. After meeting them I wanted to watch their set and - even without Kim’s bass and vocals - they absolutely blew my mind. I specifically remember hearing I’ve Been Tired and thinking it was like the greatest Violent Femmes song I’d ever heard. All resentment and competitiveness instantly vanished, and I couldn’t wait to hear them again.

I immediately cracked open the cassette and didn’t stop listening for months. I wore out my tape and begged another one from Gary. Back then, fall of 1987, I worked in a Harvard Square vintage shop called Oona’s. I worked alone in the menswear room, and I had complete control of the music. For a while I only had two tapes, A Big Star tape Evan Dando made me with the first two albums, and that Pixies demo - which I’ve heard called The Purple Tape, although I know my cover was black. It used to just blow my mind that I’d play those tapes over and over, day after day, and nobody ever even asked me what it was. I went to as many shows as I could, as they kept getting better. They usually opened for someone, and they didn’t have a big local audience. I don’t think they played the 1,000-cap Paradise until after Doolittle came out.

My favorite song on the tape was Here Comes Your Man. I never quite got used to the Doolittle version, because I knew the demo so well from hearing it literally a thousand times. The arrangement’s a little lighter, a little more country twang. Sorry, friends, everything finds its way back to country music for me, one way or another. Even Throwing Muses - my favorite from their demo was a country song Kristin and Tanya’s dad wrote about a sinkhole. It manages to be legit traditional music but still just weird enough to be Muses. Great to revisit that treasure.

1988

It surprised me how much I learned listening to the life of the Record podcast. I found it fascinating that they considered the tracks that appeared on their 4AD debut, Come On Pilgrim, and all the Purple Tape versions, many of which appeared on later albums, to be merely demos. When they talked on the podcast about working with Steve Albini at Q-Division in Boston, they considered it to be their first experience in a real studio with a real producer.

The thing is, those Fort Apache tracks that Gary Smith produced with Paul Kolderie sound great. Both Albini and Kolderie are world class engineers. Albini recorded Nirvana and The Breeders; Kolderie recorded Hole and Radiohead. Kolderie’s recordings sound how the band sounded live, which was awesome, tight, powerful. Most underground recordings in the mid-80s sounded like shit. Come On Pilgrim is not one of them. In fact, Fort Apache studios innovated by bringing high-quality recording accessible to underground bands in our scene - including The Pixies, plus Dinosaur Jr., Lemonheads, Buffalo Tom, Throwing Muses, and many others.

I learned that the Albini suggestion came from 4AD label head Ivo Watts-Russell. It’s the first project that came to him through a record company referral rather than through his own community. I remember being furious when I read disparaging comments Albini made about Surfer Rosa, calling it “a patchwork pinch loaf from a band who at their top dollar best are blandly entertaining college rock.” He came off as exceptionally humble when he expressed regret about these jackass comments, saying he’d underestimated the quality of their work.

I’ll admit I couldn’t take much Steve Albini back in his younger, mouthier days. He was so opinionated. I started early, disliking Albini’s public persona through his writing in Matter, a Chicago underground music mag from the early 80s, before I even knew he made music. He used to insult my favorite bands 40 years ago! One thing I’ve come to admire about him is that he’ll apologize for the stupid shit he used to write. That’s one among thing among many, my only regret is I never met or worked with him. Read more on topic here.

I know for a fact Gary wasn’t pleased with Ivo bringing in Albini. Gary expected to produce the album and took it hard when they went another way. He played my Blake Babies bandmates and me a pre-release mix of Surfer Rosa, describing it as a total disaster. We sat poker-faced through the playback; but the instant we were out of earshot we talked about how incredible it sounded. It was so powerful, so dynamic, so beautiful. It sounded like the future.

I remember summer of 1988, I went on a month-long Lemonheads tour in support of the album Creator (in those days I played drums in the band). Our tour was routed pretty close to The Pixies, in some of the same venues. I actually got to see them play an in-store in Minneapolis. Ben Deily and I wanted to listen to the Surfer Rosa cassette over and over, but Evan Dando got sick of it. We knew they were selling more tickets than us, and I think it stuck in his craw a little. At some point during the tour the tape disappeared, and we all suspected Evan threw it out the window.

2025

Both The Pixies and Throwing Muses were managed back then by a guy named Ken Goes. I never met him, but you’d hear his name all the time in the late 80s in Boston. He took Throwing Muses - then The Pixies - to the UK label 4AD, so that both bands broke in Europe before the U.S. We heard stories about the huge crowds they had in London, and it made the rest of us feel desperate to get over there. Buffalo Tom and The Lemonheads soon had bigger audiences overseas. Regarding Ken Goes, who really helped open those doors to us, my first thought was how do I get his job. I remember once thinking I’d love to be a music lawyer, except for the literal impossibility of actually going to law school and taking the bar exam.

I don’t claim to “have been friends with” Charles, David, Joey, and Kim at the time. We played shows together, met on numerous occasions, had pleasant exchanges. The Pixies didn’t hang out like the rest of the scene. In 1987 through 1990 you could find me at the Middle East Cafe most nights, or one of several rock clubs at least three or four nights a week when I was in town. Life didn’t change much on or off tour. I got to know lots of local musicians running into each other night after night. Even pre-fame, they didn’t really make the scene. Our encounters were backstage or after the show. At some point I became so in awe of them that I didn’t really know what to say. Fan behavior simply wasn’t part of our culture. Like with a middle school crush, sometimes we’d make an effort NOT to let on how much we loved the music.

I loved The Pixies so much, but it felt strange to have a band coming out of our scene that was clearly just as good as anything in our record collections. I remember standing in the sparse crowd at TT’s or The Rat as the band sounded perfect, thinking HOW is this not CHANGING the WORLD?! This should be SO popular, how is it not? Then I went home for Christmas break in 1989 and all my high school friends were discovering Doolittle. I wanted them to be more impressed when I told them we’d subleased our practice space to the band and Gil Norton for Doolittle pre-production, and they let us listen in. With everything going on in my life at that stage, that’s the thing I’d have been most inclined to brag about. Falling in love with that music was so consuming and intoxicating, I feel like I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since.

Being in a band is about being 100% positive you’re going to “make it,” while being completely terrified that you won’t. So inviting, so enticing to play the part. We were all well aware of the odds against it, it’s all the relatives wanted to talk about. When I fantasized my future, I imagined that we were THE band to kick-start the next revolution, the coolest of the cool. It’s disorienting to be in a local scene and doing pretty well, dreaming those dreams, then a band comes along and shows you what it looks, sounds, and feels like at a higher level. You feel like you’ve mastered three dimensions, then they show you the fourth. That happened not once but a few times - h/t to Dinosaur Jr. and Galaxie 500 at minimum, or witnessing Dando emerging as a songwriter. But for The Pixies, for those first few records, they were absolutely, without question, my favorite band.

I don’t want to take away from the awesome second life they’ve had in the 2000s through today - it’s wonderful that their music means enough for them to make a nice living. But to be honest, I kind of lost interest in The Pixies’ music before they even broke up in the early 90s. I remember mixing Blake Babies’ album Sunburn at a studio in Connecticut called Carriage House. The Pixies had just finished mixing Bossa Nova in the same studio, and one of the engineers made me a cassette copy to listen to months before the album release. I was so excited - I drove around in our van listening to it for a couple hours, feeling pretty special. I don’t think I’ve ever revisited that album. The next one, Trompe le Monde, I listened to a few times. I moved on.

It’s wild to fall in love with music that hard, to have it alter your musical DNA forever, and then at some point you just sort of lose interest. Is that a universal experience, or just fickle me? It’s happened to me more than once. I’m listening to their new (2024) album, The Night the Zombies Came, as I type. It sounds really good. I’ll bet they enjoyed making it, and I’m sure a lot of their fans are thrilled with it. It doesn’t do for me what those early records did. Nothing will ever do that again, not like that. When I scan their Spotify page and I see hundreds and hundreds of tracks, life releases, compilations, B-sides, I don’t need all that. Those first few records are on my forever playlist.

Not the Minneapolis band with Grant Hart, but a mostly forgotten local Boston act that could headline a 300 capacity club in 1987.

I was a student of the industry at the time, and part of the reason it made me angry is because I knew The Pixies had management. The manager probably wanted them to showcase that night and got Bonnie to bump us. I’m sure of that now, it’s as routine as changing the air filters. But I think I realized it then as well, and that’s what made me feel especially competitive.

Love that Podcast. The Beat Happening and Mission Of Burma episodes are outstanding as well as the Minor Threat one you mentioned.

Great narrative John. I was also a massive Pixies fan (and got to work with them when I worked at Beggars in the late 90’s, including a few Ken Goes conversations). But before I worked there, I bought tickets to see them for the first time in Atlanta. Drive down, went to play pool with my girlfriend. While playing pool, someone pinched my car…with the tickets in it (!). They found the car (stripped, with the tickets still in the glovebox) the day after the show. The band broke up for the first time several months later…